One of these obtrusive revisions mars the prose almost

immediately, in the second sentence of the episode: "His

(Stephen's) mind was not exactly what you would call

wandering..." Corraling the reference of stray pronouns

is a chore that afflicts anyone who attempts sentences of

moderate complexity, but the remedy is simple: read what you

have written, ask whether someone who does not know what you

mean would readily understand you, and change unintentionally

ambiguous pronouns to nouns. Here the clause is not even

moderately complex, but the narrator recognizes only in

retrospect that "His" possibly could refer to Bloom.

In the third paragraph the narration conveys Bloom's relief

that Corny Kelleher showed up in Nighttown when he

did––otherwise Stephen "might have been a candidate for the

accident ward or, failing that, the bridewell and an

appearance in the court next day before Mr Tobias or, he

being the solicitor rather, old Wall, he meant to say, or

Mahony which simply spelt ruin for a chap when it got

bruited about." Would Tobias have tried the case, or would it

have been Wall or Mahony? Matthew Tobias was a prosecuting

solicitor for the Dublin police rather than a magistrate, and

Thomas Wall and Daniel Mahony were divisional magistrates, so

the correction is justified. So too, arguably, is its presence

in the text, since the prose tacks so near to Bloom's own

voice––as emphasized by the phrase "he meant to say"––that it

feels almost like a snippet of conversation. But Bloom's

speech in fact is being paraphrased here, not quoted.

Shouldn't the narrator, whether omniscient or not, edit out

Bloom's momentary and completely irrelevant lapse of memory?

If this is a sin, it is a venial one. Several paragraphs

later, however, the failure to rethink and rewrite results in

egregious narrative malpractice. When Stephen goes to talk to

Corley, leaving Bloom standing apart, the narrative recounts

how Corley got the nickname Lord John. His paternal

grandfather, the story goes, married a woman whose maiden name

was Talbot, and she, rumor has it, "descended from the house

of the lords Talbot de Malahide." But this ancestor was a

member of the "house" only in a sardonically punning sense:

"her mother or aunt or some relative, a woman, as the tale

went, of extreme beauty, had enjoyed the distinction of being

in service in the washkitchen." The class difference explains

the ironic joke in "Lord John," but how would a servant have

acquired the Talbot surname, and how would a female have

passed it down to her descendants? The narrator becomes so

mired in details (what kind of blood relation it was, the

woman's beauty, which duties she performed) that he loses

sight of the essential genealogical questions.

This failure to marshall relevant facts before writing proves

merely tedious for a reader, but what happens next is

hilarious. After the narrator very formally concludes his

account ("This therefore was the reason why the still

comparatively young though dissolute man who now addressed

Stephen was spoken of by some with facetious proclivities as

Lord John Corley"), he begins a new paragraph devoted to

Corley's tale of woe. But after five sentences on the new

topic it suddenly occurs to him that he has not explained the

source of the Talbot name: "No, it was the daughter of the

mother in the washkitchen that was fostersister to the heir

of the house or else they were connected through the mother

in some way, both occurrences happening at the same time if

the whole thing wasn't a complete fabrication from start to

finish." Closer now to the promised explanation but

still not quite in possession of it, the narrative begs the

same question as before: if you can't manage to recall

something even half-coherently, why bother to mention it at

all? Worse, the new theme of Corley's poverty has been

sidetracked. It absurdly returns in one brief sentence after

the digression wraps up: "Anyhow he was all in."

It is easy to imagine Bloom saying "No, it was the daughter

of the mother in the washkitchen," but these passages do not

come close to representing his speech or even his thoughts.

While Stephen and Corley are talking and the latter's nickname

is being explicated, Bloom is some distance away, and later

the narrator makes clear that he does not know who Corley is:

"He threw an odd eye at the same time now and then at

Stephen's anything but immaculately attired interlocutor as if

he had seen that nobleman somewhere or other though where he

was not in a position to truthfully state nor had he the

remotest idea when." The word "nobleman" creates an impression

that Bloom is privy to the Talbot speculations, but this may

be yet another instance of ineptitude on the narrator's part.

However much he may have in common with Bloom the character,

he alone is responsible for writing bad fiction.

No other passages in Eumaeus match the comic

brilliance of this one, but the botching of revisions

continues. When Stephen leaves off talking to Corley and

returns to Bloom's company, there is another failure to

control pronouns: "Alluding to the encounter he said,

laughingly, Stephen, that is: / — He is down on his

luck." Here ambiguity occurs because the previous sentence has

described Bloom observing the exchange of money. Again, the

narrator fails to simply replace "he" with "Stephen." Such

usages run riot in Penelope, and they are funny there

too, but in a different way. Molly's monologue feels oral

rather than written, so the uncertain references to "he"

merely characterize her speech.

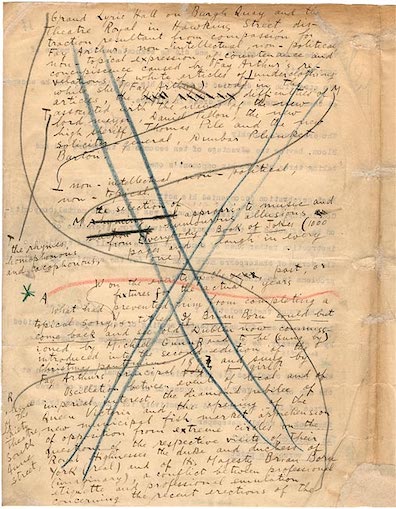

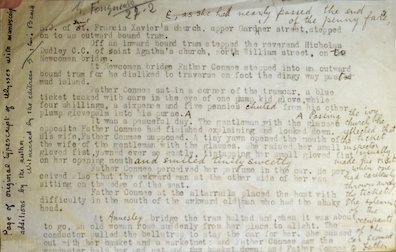

As the images posted here may suggest, Joyce was a ferocious

reviser, altering Ulysses at every stage from

manuscript to typescript to print. (The printers in Dijon must

have been driven nearly insane by the countless changes that

the Irish writer made until the last possible minute, and beyond.)

The Eumaeus narrator's difficulty with even the

simplest fundamentals of this art offers one measure of the

height of Olympian irony from which his puerile fiction is

being regarded.