Various scenes in

the

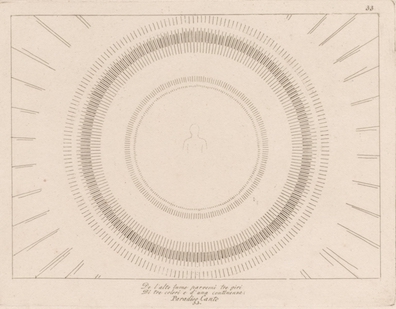

Paradiso feature concentric circles, both angels and

human souls coming together to form this shape. In the Appendix

to

Joyce and Dante: The Shaping Imagination, Mary

Reynolds offers two possible analogues to the scene in

Ithaca.

Canto 14 shows Dante in conversation with

Thomas Aquinas,

who appears as one starlike light in two bright rings circling

one another: "the holy circles showed new joy in wheeling / As

well as in their wondrous song" (23-24). Reynolds does not cite

it, but the canto opens with a similar image: Dante's thoughts,

when he has heard what Thomas has to say, move like water

ripples in a round container, "From center to rim, as from rim

to center," when it is "struck from without or from within"

(1-3). There are more concentric circles in canto 28, when Dante

sees God as an infinitesimal point of intensely bright light

surrounded by nine fiery rings of angels, revolving at different

speeds.

Reynolds' appendix merely quotes lines from Joyce's works

followed by similar ones from Dante's, without commenting, so

readers can only infer the thought processes behind her choices,

but it is hard to see what precise relevance the soul-rings or

the angel-rings could have to the rings of light on the Blooms'

bedroom ceiling. The concentric circles at the end of

Paradiso

33 offer more promising grist for the allusive mill. (Reynolds

does not cite them in her appendix, though she does mention them

earlier when she discusses Dantean circles in

Finnegans Wake.)

The canto shows two people––Dante and his final guide, St.

Bernard of Clairvaux––gazing up toward God. Bernard prays to the

Virgin Mary that "by lifting up his eyes, / he may rise higher

toward his ultimate salvation" (26-27). Dante looks "upward"

(50) to where Bernard and Mary are gazing, and his sight,

"becoming pure, / rose higher and higher through the ray of the

exalted light" (52-54). In a way that he cannot communicate or

even remember, his sight penetrates to the infinite source of

all being.

The experience culminates in a vision of three "circlings" (

giri)

somehow contained in one another:

In the deep, transparent essence of the lofty Light

there appeared to me three circles

having three colors but the same extent,

and each one seemed reflected by the other

as rainbow is by rainbow, while the third seemed fire,

equally breathed forth by one and by the other. (115-20)

Amid this mystery of Father, Son, and Holy Spirit is inscribed

the other central mystery of Christian doctrine, the unity of

God and Man in the incarnate Christ. After some gazing, the

"circling" seems, "within itself and in its very color, to be

painted with our likeness, / so that my sight was all absorbed

in it" (127, 130-32). Like a geometer attempting to square the

circle, the pilgrim struggles "to see how the image fit the

circle / and how it found its where in it" (137-38). He fails

intellectually, but a divinely granted flash of insight gives

him what he seeks, obliterating his sense of self and subsuming

his will and desire, "like wheels revolving" (143), in the Love

that turns the stars.

In Joyce's scene, Bloom and Molly gaze upward into rings of

light that are "

inconstant," with "

varying gradations

of light and shadow"––a commonly experienced effect of

lampshades. Perhaps Joyce meant to contrast these imperfect

circles with the transcendently significant ones of

Paradiso

33, or perhaps he intended to evoke Dante's impression of

colored lights mysteriously shimmering into one another while

remaining separate. Similar questions of correspondence or

non-correspondence are raised by the images' referents. As he

looks at the lights Dante struggles to understand the Trinity

and the Incarnation. The Blooms, by contrast, are thinking about

what Bloom has been doing all day (such questions about Molly's

day remain unasked), about Molly's inquisitorial interest in

such matters ever since Milly's first period, and about the sad

state of their sexual relationship since the death of Rudy.

Every Joycean allusion invites readers to ask how far the

correspondence may extend. Does the

Ithaca passage offer

an analogue to Dante's effort to see how the human image is

inscribed in the divine one? It probably does, since both

Leopold and Marion are asking themselves whether they still have

a place in this marriage, and are struggling to see how they fit

in it. Does some Trinitarian relationship figure in their

thoughts? This seems less certain, but possible. Just before the

long paragraph devoted to Bloom's day, Molly's interrogation,

Milly's menstruation, Rudy's death, and sex, a short one has

asked what is the "salient point" of Bloom's narration. Answer:

"Stephen Dedalus." Husband and wife may well be wondering how

Stephen could fit into their marital circle. In

Eumaeus

and

Ithaca Bloom thinks that bringing the young man into

his house might solve certain problems, and in

Penelope Molly

entertains similar thoughts. Stephen shows no sign of wanting

any part in a triangle, sexual or otherwise, but for both Blooms

it seems to hold out some hope of marital rejuvenation.

Or, to consider a different Trinity, could Milly be contained in

the circles? The narrative has just described how her pubescence

has altered behavioral patterns in the marriage, and earlier in

Ithaca Bloom has recalled a time when a drop of his

daughter's spit made "

concentric circles of waterrings,"

precisely like the image at the beginning of canto 14. A

Bloom-Molly-Milly trinity on the ceiling would constitute an

emblem of the current family unit. A Bloom-Molly-Stephen trinity

would convey the potential union of the novel's three

protagonists: Father, Mother, and surrogate Son.

Such human mysteries may prove as impossible to parse out as

Dante's theological questions, but in both works the overall

promise of the circles seems clear enough. Dante's offer him

insight into the Love that moves the stars. Joyce's, if they are

cut from the same cloth, suggest that the Blooms still see

something worth saving in their marriage. Dante's vision

requires that he demonstrate his understanding of faith (canto

24), hope (25), and love (26). With enough of these three

virtues, the Blooms too may find their way through a rough patch

to a secular approximation of heaven.

Ithaca begins with Bloom and Stephen visualized from

far above charting squiggly "parallel courses" from the

Customhouse to Eccles Street. It ends with Bloom and Molly

tracing lines through unbounded space on squiggly parallel

courses described by the earth's rotation, revolution, and

inclination "at an angle of 45° to the terrestrial equator"

and positioned 180° to one another in the bed. The scientific

worldview implicit in the chapter's mathematics and astronomy

provides a kind of framing context for Joyce's appropriation

of Dante's image, whose parallel circles embody the perfection

of changeless being. In the world of change nothing is

perfect, but even in shadows playing on a ceiling life holds

out provisional promises of fulfillment.