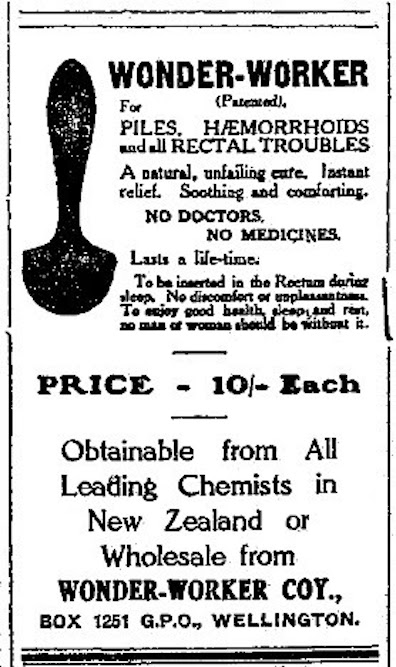

In a JJON note, Robert Janusko reports that a product

called the Wonder Worker was "listed in the London Gazette,

4 May 1928 as available from 'Frederick Adolph Werner; Patent

Medical Appliance; Coventry House, South Place, London, E.C.

2'." An advertisement published in the London Daily

Express in 1922, which was discovered by John Simpson

and reproduced on another JJON page by Ronan Crowley,

lists the same address, which corresponds closely with the

address listed in Ithaca as the source of the

advertisement: "Wonderworker, Coventry House, South Place,

London E. C." The 1922 ad mentions a "booklet" which

interested readers could obtain to learn more about the

product––no doubt the inspiration for Joyce's "prospectus."

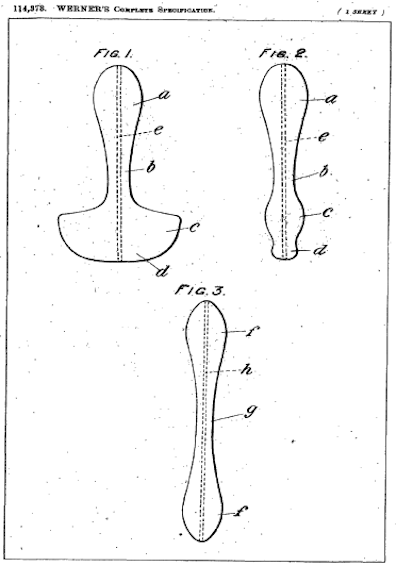

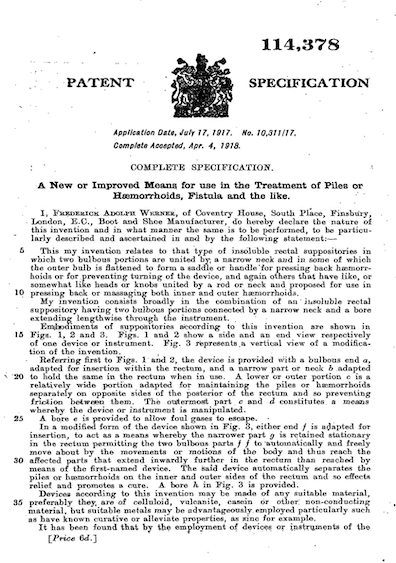

Janusko tracked down Werner's July 1917 patent application,

which was approved in April 1918, as well as a second

application in 1924-25. The first document identifies the

device as belonging to "that type of insoluble rectal

suppositories in which two bulbous portions are united by a

narrow neck," but Werner's invention additionally features "a

bore extending lengthwise through the instrument" (depicted

with dotted lines in Figs. 1, 2, and 3) "to allow foul gases

to escape." The shorter and wider "bulbous portion" of the

device is "adapted for maintaining the piles or hæmorrhoids

separately on opposite sides of the posterior of the rectum

and so preventing friction between them." The second patent

application describes an improved version that "consists in

dispensing with the lengthwise bore […] and shaping the

several parts of such an appliance that its dimensions

correspond, or approximately correspond, and comfortably adapt

themselves to the anatomical dimensions of the affected parts

of the human body."

Readers of Calypso learn that Bloom periodically

suffers from "piles"

(i.e., hemorrhoids) and thinks about how to keep them from

flaring up, but it seems that his request for a prospectus has

been prompted also by gassy intestines. In Sirens, as

cider wreaks havoc on his guts and he searches for ways to

release the gas without embarrassment, he thinks, "Wait.

That wonderworker if I had." In Circe he ponders

the unfortunate mental and physical things that sleep can

bring out of a human being: "Steel wine is said to cure

snoring. For the rest there is that English invention,

pamphlet of which I received some days ago, incorrectly

addressed. It claims to afford a noiseless, inoffensive

vent."

The absurdity of keeping an appliance lodged in one's rectum

only to eliminate offensive fart sounds (and wouldn't free

passage of gases risk the release of offensive smells?) gives

way in Ithaca to a wildly comic parody of the device's

advertisements: "It heals and soothes while you sleep, in

case of trouble in breaking wind, assists nature in the most

formidable way, insuring instant relief in discharge of

gases, keeping parts clean and free natural action, an

initial outlay of 7/6 making a new man of you and life worth

living. Ladies find Wonderworker especially useful, a pleasant

surprise when they note delightful result like a cool drink of

fresh spring water on a sultry summer's day. Recommend it to

your lady and gentlemen friends, lasts a lifetime." The

"testimonials" from various satisfied customers include a

soldier who exclaims, "What a pity the government did not

supply our men with wonderworkers during the South African

campaign! What a relief it would have been!"

This delightful parody reflects the popularity that the

invention gained among British men and women. Janusko quotes

from Norman Lewis's 1985 autobiography Jackdaw Cake:

"More extraordinary even was the addiction to the use of the

Wonder Worker. This was a small spade-shaped Bakelite

contraption designed for insertion in the rectum, intended

originally as a cure for haemorrhoids but later accepted for

its talismanic properties in the treatment of all human ills.

[Joyce calls it a "thaumaturgic remedy," a miracle

cure.] Innumerable intelligent people, including the cream of

local society such as the Bowlses, Orr-Lewis––who had survived

the Titanic disaster––the fearful virago Lady Meux––once a

Gaiety Girl––probably General French who had presided over the

massacres at Ypres, possibly even Miss Tupperton herself, were

walking around with these things stuck up their bottoms" (53).

The most hilarious detail in Joyce's parody is the brief

instruction, "Insert long round end." In addition to

playing on the squeamish discomfort that prospective buyers

must have felt about this product, the sentence intensifies

one's inescapable sense that the Wonderworker resembles an

anal dildo or butt plug. The vaguely sexual aura of the device

keeps company in Ithaca with the error that has caused

someone to address the prospectus to "Mrs L. Bloom" and

to enclose a note beginning, "Dear Madam." No doubt

embarrassed by his interest in the product, Bloom seems to

have inadvertently invited misapprehension by abbreviating his

first name to "L." But by this point in the novel, readers

schooled in his use of pseudonyms to receive illicit sexual

correspondence (Lotus Eaters) and his dark fantasies of

being sexually violated (Circe) will inevitably be

tempted to speculate whether the Wonderworker quells desires

as effectively as discomforts.

In his note, Ronan Crowley suggests that Joyce was also

thinking about the transgressiveness of writing about matters

rectal, anal, and excremental. In September 1916 he wrote to

Yeats, "‘I can never thank you enough for having brought me

into relations with your friend Ezra Pound who is indeed a

wonder worker'." Since Werner's invention had not yet

been patented, marketed, and advertised, there can be no

reason to suppose that this sentence contains a veiled

reference to it. Pound was simply showing himself to be a

wonder worker––a thaumaturge––in his dogged devotion to

getting Joyce's fictions published. But a couple of years

later, in March 1918, Pound wrote to say that he felt

compelled to delete the account of Bloom's defecation from the

version of Calypso published in The Egoist. He

also objected to the fart that concludes Sirens. Pound

feared running afoul of Britain's harshly adjudicated

obscenity laws, and he felt that shoving distasteful matters

into readers' faces was aesthetic overkill––"bad art."

In the 1922 edition of the novel Joyce alluded to this

exchange, and to his eventual triumph over such censorship, by

having Bloom think of Philip Beaufoy's story that they will "Print

anything now." Pound's aesthetic criticism clearly

provoked him. In a draft of Circe he had Bloom say of

Beaufoy's story, "It is bad art, not true to life." The

published version of the chapter toned this down but kept the

phrase "bad art." Although Circe describes the

Wonder Worker only as "that English invention," Joyce did name

the "wonderworker" in the chapter where Bloom loudly

farts, and then again in Ithaca where it is called a

"thaumaturgic remedy"––details that surely contain some sly

reference to the American genius who had done so much to help

him get published.

It is hard to know exactly what to make of these buried

allusions, but the intention cannot be entirely friendly. In

1918 Pound had insisted that Joyce tell the truth without

including offensive material. In the version of Ulysses published

in 1922 the impulse to give "inoffensive vent" is associated

with a wonderworking rectal suppository.