Two questions and

answers introduce densely layered allusions:

In what order of

precedence, with what attendant ceremony was the exodus from

the house of bondage to the wilderness of inhabitation

effected?

Lighted Candle in Stick borne by

BLOOM

Diaconal Hat on Ashplant borne by

STEPHEN

With what intonation secreto

of what commemorative psalm?

The 113th, modus

peregrinus: In exitu Israël de Egypto: domus Jacob de populo

barbaro.

At the Seder meal of

Passover,

when Jews celebrate their liberation from Egyptian captivity,

the head of each household, assisted by his grown sons, intones

sentences from the Haggadah telling the Exodus story of the

night when an angel of God killed the firstborn sons of Egypt,

convincing the pharaoh to let his Hebrew slaves depart into the

wilderness of the Sinai peninsula. In

Aeolus Bloom

slightly misremembers the language he learned from his father:

"All that long business about that brought us out of the land of

Egypt and into the house of bondage."

Ithaca corrects

the preposition ("

the exodus from the house of

bondage to the wilderness of inhabitation"), and now Bloom

plays the patriarch, taking the "

order of precedence"

while Stephen follows behind him. Are they actually conducting a

mock ceremony? The "

intonation" of a sacred text suggests

that in fact they are.

The biblical verse chanted, "

In exitu Israël de Egypto:

domus Jacob de populo barbaro" is rendered in the

King James Bible as "When Israel went out of Egypt, the house of

Jacob from a people of strange language" (Psalms 114:1). This

verse is indeed featured in the Hebrew Haggadah and the Tanakh

on which it draws, but

Ithaca quotes it in the Latin of

the Vulgate Bible with which Stephen is familiar, where the

psalm is numbered 113. "

The 113th" psalm makes up part of

the Vespers service, a set of evening prayers usually performed

around sunset. Here it is not only chanted in Latin but

introduced by two Latin terms, suggesting that Stephen rather

than Bloom is doing the intoning. Gifford notes that "

secreto"

(secret, separated, set apart) is a direction in the

Layman's

Missal that is a possible source for Stephen's

Liliata rutilantium

prayer, indicating that a priest speaks the words "in a low

voice."

Joyce criticism has never satisfactorily explained the second

term, "

modus peregrinus." Gifford offers the gloss

"mode of going abroad," while Slote says "foreign manner." Both

translations of

peregrinus are possible: in ancient Rome

the word denoted a subject of the empire who was not a Roman

citizen (a foreigner), and by medieval times it had come to mean

something more like "traveler" (one going abroad). Gifford's

reading in particular seems well suited to the fact that Stephen

and Bloom, like the ancient Hebrews, are exiting the house and

venturing into the "

wilderness." But "mode" and "manner"

are not among the primary meanings of

modus, and neither

translation suggests why the narrative should offer this phrase

in Latin.

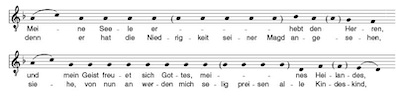

The religious context of Stephen's chant does. Gregorian chant

is performed in various "modes" (scales of note intervals) that

originated in antiquity. There are eight standard modes (Dorian,

Phrygian, Lydian, etc.), but Psalm 113 has traditionally been

sung in an alternate mode called

tonus peregrinus

or "wandering tone," so called because its "tenor" or "reciting

tone," the note on which most of a psalm verse is sung, varies

from the first half of the verse to the second––it wanders. In

Catholic church music the

peregrinus mode is associated

with Psalm 113 more than any other biblical text. (Whether this

pairing came about because the text itself is about wandering,

or by coincidence, I cannot say.) Perhaps Joyce misremembered

the phrase "wandering note" as "wandering mode" (it does name a

mode, after all), or perhaps by substituting

modus for

tonus he intended to evoke a second meaning, "mode of

going abroad."

It appears, then, that as Bloom leads the way to the back door

of his house he is also leading Stephen in a fanciful religious

rite, having somehow proposed that they conduct a Passover

exodus from Egypt, while Stephen plays along by chanting some

language appropriate to this theme from the Latin rituals of his

church. Like the Seder's patriarchal setting of a father leading

his sons, Catholic rites involve a fatherly "celebrant" (priest)

and his son-like assistants (deacons and altar boys). Stephen's

"

Diaconal" hat indicates that he is playing a deacon to

Bloom's celebrant, servant to his server, son to his father––an

accustomed role for him. His

choice of a Latin psalm text to complement a Jewish service

continues the sharing of ethnic, religious, and linguistic lore

that the two men engaged in earlier in

Ithaca. Indeed,

in that section of the chapter Bloom chanted the first two lines

of a Hebrew anthem: "

Kolod balejwaw pnimah / Nefesch, jehudi,

homijah." Now Stephen returns the favor.

§ Readers

who want to limit their diet of overdetermined signification to

what Joyce's words minimally require may wish to stop here, but

there is probably more to unpack from this passage. Three of its

details––the candle, the psalm, and the word

peregrinus––will

resonate for those who know Dante's

Purgatorio. The last

of these is responsible for the phrase often used to refer to

the central character of the

Divine Comedy, "Dante the

pilgrim," but Dante makes clear in an earlier work that

peregrino

does not primarily mean pilgrim. Section 40 of the

Vita

Nuova observes that it can refer to people making

devotional pilgrimages to Compostela (they are

peregrini,

while people traveling to Jerusalem are

palmieri and

those going to Rome are

romei), but this is a special

case. The general sense is simply "traveler": "

chiunque è

fuori de la sua patria," someone far away from home. There

are seven uses of the word in the

Divine Comedy, only

one of which refers to travelers on a religious mission. Five

uses come in the

Purgatorio, the poem about people

halfway between earth and heaven (dead souls) and halfway

between hell and heaven (Dante). All of them (2.63, 8.4, 9.16,

13.96, 23.16) evoke the condition of leaving home, being on the

road, venturesome, nostalgic, lost, free.

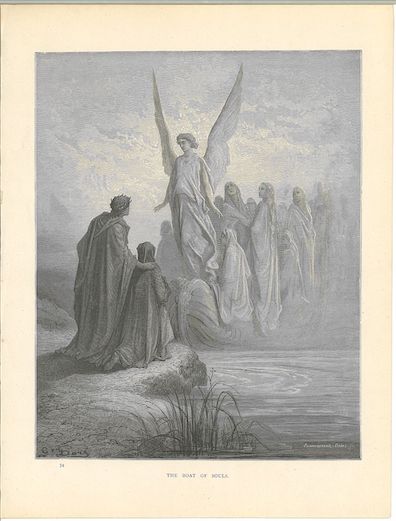

The usage relevant to

Ithaca comes in canto 2, when a

boat arrives at the base of the mountain carrying recently

deceased people who are singing Stephen's psalm: "

In exitu

Isräel de Aegypto" (46). It is clear why

Dante has them chant these words. In the letter to Cangrande

della Scala in which he explains to his patron his purposes in

writing the

Comedy, he takes the opening words of Psalm

113 as a text for illustrating the allegorical method of the

entire poem: the verse refers literally to the Hebrews' exodus

from Egypt but allegorically to the human soul's delivery from

sin. The souls in the boat are leaving their earthly lives to

enter a new realm, and they are "strangers to the place, gazing

about / as though encountering new things" (2.53-54). Not

knowing how to go up the mountain they ask Dante and Virgil for

directions, but Virgil replies, "'Perhaps you think / we are

familiar with this place, / but

we are strangers (peregrin)

like yourselves. / We came but now, a little while before

you, / by another road so rough and harsh / that now the climb

to us will seem a pastime'" (61-66). The canto, then, links the

figure of the

peregrinus to the 113th Psalm, just as

Joyce does in

Ithaca.

Virgil's words about traveling a "rough and harsh" road refer to

the trip that he and Dante took through Hell, at the end of

which they emerged to

behold the

stars––an event that Joyce will echo several sentences

later in

Ithaca. Between the end of

Inferno and

the second canto of

Purgatorio, there is another image

relevant to Joyce's exodus scene. At the base of the mountain,

its guardian Cato challenges Dante and Virgil: "What souls are

you to have fled the eternal prison...

Who was your guide or

who your lantern / to lead you forth from that deep night

/ which steeps the vale of hell in darkness?" (1.40, 43-45). In

Dante's cosmos people do not ascend to God by their own power

and understanding; everyone requires an intermediary guide.

Dante's lantern in the poem is Virgil, and he is not alone in

this respect. In

Purgatorio 22 he asks the ancient poet

Statius how he found the true faith when his works gave no

evidence of it: "what sun,

what candles dispelled your

darkness so that afterwards / you hoisted sail, following

the fisherman?" (61-63). Statius replies that it was the

writings of Virgil: "You were as

one who goes by night,

carrying / the light behind him––it is no help to him, but

instructs all those who follow" (67-69). These lines adapt St.

Augustine's description of the Jews as a people who "carried in

your hands the lamp of the law in order to show the way to

others while you remained in the darkness." Now it is a pagan

Roman poet who reveals the light of revelation to others while

not benefiting himself.

Amid all the other Dantean echoes in this part of

Ithaca,

it is hard not to hear an allusion to Virgil lighting the way

for others in Joyce's picture of a Jew leading Stephen out of

his house with a "

Lighted Candle." As an uneducated

salesman Bloom may seem an unlikely guide for Stephen, but that

is true of Virgil as well: as a poet of pre-Christian antiquity

he is an unlikely choice to show Dante the path to salvation.

Both the

Inferno and the

Purgatorio play

repeatedly on the pathos of his illuminating the way for others

while himself being condemned to Hell for not knowing God. As

Stephen follows his host to the back door of the Eccles Street

house, the allusion suggests that this Catholic apostate has

things to learn from a Jewish nonbeliever. Both Dubliners are

Dante-like exiles, lonely

peregrini

who have wandered far from the values of their native

communities. They hail from different pasts, and the parting in

Bloom's garden suggests that they are bound for different

futures as well, but their performance of a mock ritual––one

that celebrates exile––proclaims a meeting of kindred spirits

like that of the two poets Dante and Virgil.

These Dantean echoes surely represent the author's own

construction of the scene, layered on top of his characters'

fanciful enactment of a Passover ceremony. It is Joyce, not

Bloom or Stephen, who imagines the one as an important

paternal inspiration for the other and who suggests

simultaneously that they may never become friends or familial

relations. This discernment of difference in the show of

symbolic unity is also implicit in the detail "house of

bondage." For Bloom, the phrase reflects a miserable

private preoccupation. Given the meek subservience he displays

toward Molly, and her adultery on June 16, his mistake in Aeolus

may have been a Freudian slip suggesting that he sees his

house as a locus of entrapment. For Stephen, who has been

offered a place to sleep and chooses instead to wander off

into the night, the phrase may suggest entrapment of a

different kind. He has, after all, recited for Bloom the story

of the boy who went into a Jew's house to retrieve a ball and

had his head cut off with a penknife by the Jew's daughter.

Despite all they have shared in Ithaca the two men are

running along separate tracks.