All three cantiche of the Divine Comedy

conclude with the word stelle, "stars." In canto 34 of

the Inferno Dante and Virgil end their dark tour of

Hell, passing by Satan at the bottom of the ninth circle and

climbing up a narrow channel "to find again the world of

light" (134). They get "far enough to see, through a round

opening, / a few of those fair things the heavens bear. /

Then we came forth, to see again the stars" (137-39).

Joyce echoes these lines twice. In addition to the full vision

of the night sky evoked in "The heaventree of stars," he

recalls the tiny round opening of lines 137-38 by suggesting

that the Milky Way would be "discernible by daylight by

an observer placed at the lower end of a cylindrical

vertical shaft 5000 ft deep sunk from the surface towards

the centre of the earth." Readers of the Inferno

will recall that "the centre of the earth," where Satan is

embedded in the ice, is where Dante's ascent to the light

begins.

In Dante's poem the heavenly bodies are omnipresent

companions. The passage of day and night and the cycling of

the seasons are known by the relative positions of the sun,

planets, and stars. Both Virgil and Dante display exacting and

comprehensive knowledge of medieval astronomy, and the poet

supplements scientific understanding with pervasive poetic

symbolism. (To cite one of many examples, the four stars that

he sees in canto 1 of Purgatorio are not only a

constellation, probably the Southern Cross, but also emblems

of the four cardinal virtues possessed by Adam and Eve.) Even

Dante's science is fanciful. Astronomy was inseparable from

astrology in medieval thinking, because causative divine

"influences" were thought to descend from the mind of God,

through particular constellations of stars and then through

the spheres of individual planets, to shape events on earth

and mold the dispositions of human beings.

In addition to their functions in time-keeping, moral

allegory, and etiology, Dante's heavenly bodies constitute a

vast mechanical apparatus, rotating around the earth in

invisible crystalline spheres according to the Ptolemaic

cosmological teachings of his time. In Paradiso he

ascends to his vision of God by rising through these

crystalline spheres in a fixed hierarchical order: the Moon,

Mercury, Venus, the Sun, Mars, Jupiter, Saturn. After entering

the sphere which holds all of the "fixed stars" (the ones that

do not move in relation to one another), and the Primum Mobile

that imparts motion to all the others, Dante is in the

Empyrean where God dwells. Although he does not use Joyce's

metaphor of a tree, the stars are for him quite literally a

structure through which he climbs to the highest heaven.

Joyce made Bloom, like Dante, an amateur stargazer and

endowed him with the impressive fund of astronomical knowledge

displayed in Ithaca. The word "heaventree" suggests

that, despite his atheism, Bloom is sufficiently awed by the

"spectacle" of the night sky to imagine the kind of majestic

divine order proclaimed in Dante's poem. But his thoughts do

not lead to contemplation of a divine creator. Unlike Dante,

who launches his fictive avatar from the summit of the

enormous mountain of Purgatory to jet upward, Bloom is

"Conscious that the human organism, normally capable of

sustaining an atmospheric pressure of 19 tons, when elevated

to a considerable altitude in the terrestrial atmosphere

suffered with arithmetical progression of intensity, according

as the line of demarcation between troposphere and

stratosphere was approximated, from nasal hemorrhage, impeded

respiration and vertigo." He might have added cerebral edema,

pulmonary edema, heart attack, and frostbite. Mountaineers

call this region the death zone.

In a striking echo of Dante's ascent through the nested

orbits of the solar system, Bloom reasons that it is

conceivable that "a more adaptable and differently

anatomically constructed race of beings might subsist

otherwise under Martian, Mercurial, Venereal, Jovian,

Saturnian, Neptunian or Uranian sufficient and

equivalent conditions." He leaves out the sun and moon, no

longer regarded as planets as in Dante's time, but adds

Neptune, discovered in 1846, and Uranus, known since 1781,

keeping the number of planets the same. Bloom reflects,

however, that living on celestial worlds would not by itself

bring humanity any closer to divinity. The narrative asks

whether "the inhabitability of the planets and their

satellites" by such an evolved "race" would render the problem

of "social and moral redemption of said race by a redeemer,

easier of solution?" The answer is no: "an apogean humanity of

beings created in varying forms with finite differences

resulting similar to the whole and to one another would

probably there as here remain inalterably and inalienably

attached to vanities, to vanities of vanities and to all that

is vanity."

Pondering such questions posed by the celestial display, Bloom

concludes "That it was not a heaventree, not a heavengrot, not

a heavenbeast, not a heavenman. That it was a Utopia, there being no known

method from the known to the unknown: an infinity renderable

equally finite by the suppositious apposition of one or more

bodies equally of the same and of different magnitudes: a

mobility of illusory forms immobilised in space, remobilised

in air: a past which possibly had ceased to exist as a present

before its probable spectators had entered actual present

existence." Not only do the planets and stars offer no way

"from the known to the unknown," but they may not even exist.

We apprehend them as light emitted eons earlier from objects

that quite possibly have ceased to be. Dante's medieval

science dealt in permanent knowable substances. Modern science

trades in evanescences, ambiguous manifestations, distant

measurements, unimaginable immensities.

Having decided that scientific analysis trumps poetic fancy,

Bloom nevertheless retains the awed appreciation of beauty

that he felt when he first stepped into the garden. The

narrative asks, "Was he more convinced of the esthetic value

of the spectacle?" The answer: "Indubitably in consequence of

the reiterated examples of poets in the delirium of the frenzy

of attachment or in the abasement of rejection invoking ardent

sympathetic constellations or the frigidity of the satellite

of their planet." Human beings will still feel what they feel

and project it onto the heavens, no matter how ruthlessly

reason deflates their extravagant imaginations.

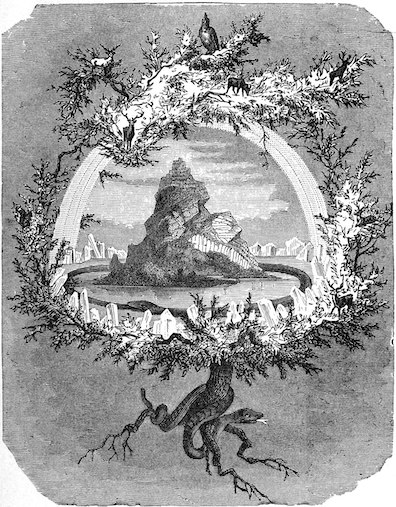

In a JJON article, John Simpson observes that

Joyce probably did not coin the word "heaventree" and could

have run across several fanciful accounts of such an entity.

The OED records that as early as 1835 the word was

being used for a plant, Ailanthus altissima, which

Malay speakers had described as "tree reaching to the sky." A

related but rarer meaning, documented in an 1865 work, stemmed

from Malaysian and Polynesian myths that envisioned “a

mythical tree growing from the underworld, through the earth,

and up to heaven." Scandinavian mythology too tells of such a

tree. Yggdrasil, the sacred ash of the Norse eddas

which may have given rise to the story of Jack and the

beanstalk, reaches from the underworld into the heavens.

Joyce might even have found the stars overlaid on such a

celestial tree. In an 1858 poem, The Heroes of the Last

Lustre, American journalist and poet John Flavel

Mines painted a metaphorical image of the night sky:

"Resplendent stars, in purple meadow trembling; / Leaves of

the great Heaven tree." These sources cited in Simpson's note

may well account for Joyce's strikingly unusual word and even

for the radiant imagery of the sentence in which it appears.

But the following sections of Ithaca show the

mythological image being scrutinized, and ultimately

discarded, by astronomical meditations that update and subvert

the cosmology of Dante.