Slote, Mamigonian, and Turner note that "Aristotle claimed in

the De Generatione Animalium that stars could be seen

in the daytime if an observer were placed at the bottom of a

deep shaft or well (708b21)." After remarking that various

people have disproved the idea, starting with Robert Hooke in

the 17th century, they quote from chapter 20 of the

Pickwick Papers, arguing that Joyce's

passage "follows from" one in which Dickens describes four men

"catching as favourable glimpses of heaven's light and

heaven's sun, in the course of their daily labours, as a man

might hope to do, were he placed at the bottom of a reasonably

deep well; and without the opportunity of perceiving the stars

in the day-time, which the latter secluded situation affords."

The Dickens passage predicts Joyce's only vaguely. A

statement of the idea by Sir Robert Ball, noted by

Harry Manos in "Physics in James Joyce's Ulysses,"

The Physics Teacher 60 (1922): 6-10, does so much more

precisely. In Lestrygonians Bloom calls Ball's Story

of the Heavens (1886) that "Fascinating little book,"

and Ithaca reveals that it sits on his bookshelf. In a

passage of his later book Starland (1899), Ball claims

that stars can be seen in daylight, after imagining a quite

long hole in the earth:

These groups of stars extend all around the sky.

They are not only over our heads and on all sides down to the

horizon, but if we could dig a deep hole through the

earth, coming out somewhere near New Zealand, and if we

then looked through, we should see that there was another

vault of stars beneath us. We stand on our comparatively

little earth in what seems the centre of this great universe

of stars all around. It is true we do not often see the

stars in broad daylight, but they are there

nevertheless. The blaze of sunlight makes them invisible. A

good telescope will always show the stars, and even without a

telescope they can sometimes be seen in daylight in

rather an odd way. If you can obtain a glimpse of the blue sky

on a fine day from the bottom of a coal pit, stars are often

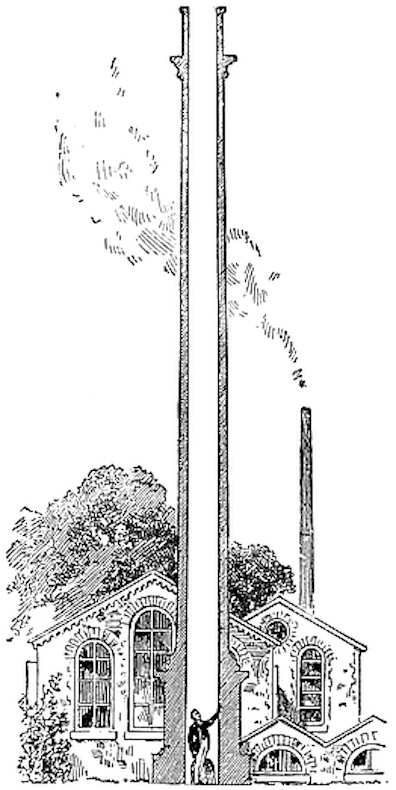

visible. The top of the shaft is, however, generally

obstructed by the machinery for hoisting up the coal, but the

stars may be seen occasionally through the tall chimney

attached to a manufactory when an opportune disuse of the

chimney permits of the observation being made (Fig. 24).

The fact is that the long tube has the effect of completely

screening from the eye the direct light of the sun. The eye

thus becomes more sensitive, and the feeble light from the

stars can make its impression, and produce vision. (59-60)

Ball's thought experiment of a hole bored all the way through

the earth is followed by a more pragmatic claim that stars can

be seen in daytime from coal mines and factory chimneys. But the

more extravagant idea offers a suggestive context for Bloom's

impossibly long "vertical shaft," and Ball's use of the words "

daylight"

and "

shaft" confirm that

Starland must be Joyce's

primary source.

I do not know of any inspiration for Bloom's length of nearly

one mile, but the idea of such a long shaft descending "from

the surface towards the centre of the earth" does appear

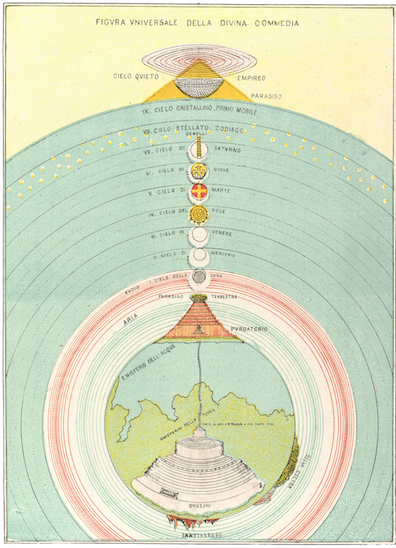

in one famous literary work. The Divine Comedy

pictures the earth as holding land in the northern hemisphere

and water in the southern, with Jerusalem in the former

diametrically opposed to the purgatorial mountain in the

latter. Along one half of this immense diameter lies a tunnel

through which Virgil and Dante climb from the earth's center

back to the surface in the final canto of the Inferno.

Its length, according to Dante's own science, would be more

than 3,000 miles, but he does not dwell on the impossibility

of covering all this ground in the short time he gives his

character. He merely shows himself arriving at a point close

enough to the surface to glimpse the stars through a pinprick

in the earth's crust:

we climbed up, he first and I behind him,

far enough to see, through a round opening,

a few of those fair things the heavens bear.

Then we came forth, to see again the stars. (34.136-39)

As Joyce surely knew, Ball's fancy of a tube bored from

Britain to New Zealand finds a remarkably close analogue in

Dante's plumb line from Jerusalem to Purgatory, and both

writers imagine gazing from such a tube through a round

aperture (un pertugio tondo). Readers who feel inclined

to dismiss the correspondences as merely coincidental should

consider what happens immediately before this in Ithaca.

Just as Virgil leads Dante out of the darkness of Hell via a

tunnel, "he first and I behind him," Bloom leads

Stephen out of the darkened "house of bondage" on Eccles

Street into his back yard via a hallway and a "door of

egress": "first the host, then the guest, emerged silently,

doubly dark, from obscurity by a passage from the rere of

the house into the penumbra of the garden." Dante passes

from the darkness of Hell to the starlit surface of the earth

where he and Virgil behold "those fair things the heavens

bear." Bloom and Stephen––"doubly dark," because both

are dressed in black––go out into the shadowy garden to behold

"The heaventree of stars."

These echoes of Dante are quite precise (though no one has

ever noticed them until now), and they are reinforced by

others. As the two men exit the house Stephen chants the first

verse of Vulgate Psalm 113 (114 in other versions of the

Bible) in modus peregrinus––details that evoke the beginning

of Purgatorio as Dante puts the "house of

bondage" behind him and begins the next phase of his journey.

"Heaventree" loosely suggests the celestial architecture

through which Dante ascends to God in Paradiso. Three

paragraphs after this word, Bloom's fancy of human beings

living on the seven planets of the solar system much more

exactly echoes the seven spheres of the solar

system (the first of nine celestial spheres) in that

poem. Joyce's dense clustering of Dantean allusions in this

part of Ithaca suggests a deliberate and intricate

intertextual design.