The text gives less obvious encouragement to reading symbolic

significance into Mulligan's "yellow dressinggown" than it

does with mirrors and razors,

but in Christian countries this color had long been associated

with heresy and treachery. In Circe these

associations settle on Bloom.

Quoting George Ferguson's Signs and Symbols in Christian

Art (1954), Gifford notes that "the traitor Judas is

frequently painted in a garment of dingy yellow. In the Middle

Ages heretics were obliged to wear yellow" (153). After the

Fourth Lateran Council in 1215, some countries forced Jews to

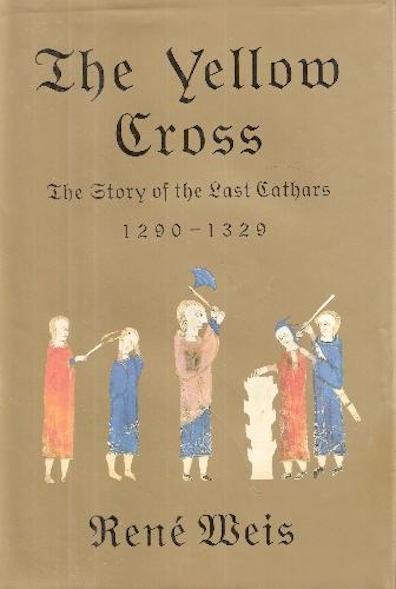

wear a yellow badge on their clothing. After the Albigensian

Crusade ended in 1229, the Papal Inquisition of Pope Gregory

IX decreed that all remaining Cathars would wear yellow

crosses on their clothing as a similar badge of shame. This

practice was part of a broad cultural effort to stigmatize

certain groups. (In some countries paupers who had received

relief from the parish were made to wear red or blue badges on

one shoulder, in order to make seeking such relief

unappealing.) Islamic countries with large Jewish and

Christian populations had done the same thing in earlier

centuries. In the 20th century, the Nazis in Germany revived

these medieval badges of shame, forcing Jews to sew yellow

stars of David on their clothes and making homosexuals wear

pink triangles.

Since Stephen associates Mulligan with heresy later in Telemachus,

the fact that Buck likes to wear yellow clothing is

very suggestive. Later in Telemachus we learn that

his waistcoat

too is "primrose" colored.

In Circe, Bloom is immolated by an Irish version

of the Inquisition after being given such clothes to wear.

Brother Buzz "Invests Bloom in a yellow habit with

embroidery of painted flames and high pointed hat. He places

a bag of gunpowder round his neck and hands him over to the

civil power," saying, "Forgive him his trespasses." Of

course, it is Bloom rather than Mulligan that most Dubliners

would see as a heretic. Half-Jewish by ancestry (his father

converted before his marriage, but tried to instill Jewish

traditions in his son), half-Protestant by affiliation (raised

in the Church of Ireland and a Freemason later in life),

Catholic only nominally (he converted in order to marry

Molly), and fully atheistical by temperament (he disbelieves

in the incorporeal

soul, dying in a state of grace, converting

unbelievers, and a host of other Christian teachings),

Bloom is quite inevitably an object of suspicion to most of

the Irishmen he meets.