Readers of "Grace" meet Mr. Kernan lying "curled up at the

foot of the stairs down which he had fallen," in "the filth

and ooze" on the floor of a pub's lavatory, with part of his

tongue bitten off. (In Penelope Molly calls him "that

drunken little barrelly man that bit his tongue off falling

down the mens WC drunk in some place or other.") Some of

his friends decide that he has hit bottom as an alcoholic and

undertake to "make a new man of him" by convincing him to

attend a religious retreat. Jack Power, Charley M'Coy, and Martin Cunningham are

aware that "Mr Kernan came of Protestant stock and, though he

had been converted to the Catholic faith at the time of his

marriage, he had not been in the

pale of the Church for twenty years. He was fond,

moreover, of giving side-thrusts at Catholicism." To encourage

compliance, they sing the praises of the Jesuit priest who will be

conducting the service, and of the Catholic church more

generally.

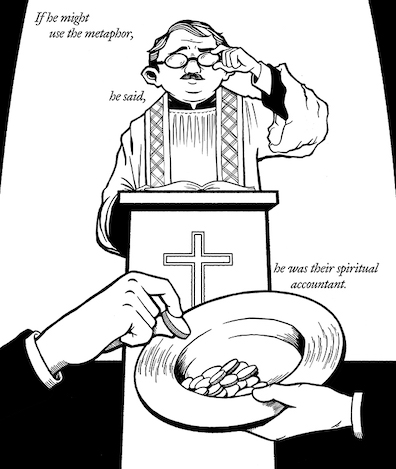

Many withering ironies attend this campaign, not least of

them the campaigners' assurances that the retreat is "for

business men," and that Father Purdon is "a man of the world

like ourselves." Sure enough, the good father's sermon

concerns the exceedingly strange biblical text, Luke 16:8-9,

in which Jesus says that the children of this world are wiser

than the children of light, commanding his followers to "make

unto yourselves friends of the mammon of iniquity." This

passage, the priest says, is "a text for business men and

professional men," offering help to "those whose lot it was to

lead the life of the world." As Father Purdon preaches, a "speck of red light" burns over

the altar in the Saint Francis Xavier church, signifying

the presence of the Blessed Sacrament in the tabernacle.

Purdon Street ran through Dublin's red-light district, the Monto. The book's theme of

simony sounds very strongly here.

Tom Kernan is indeed a man of business: he tastes and sells

tea. In Lotus Eaters, Bloom thinks of "Tea. Must

get some from Tom Kernan. Couldn't ask him at a funeral,

though." Wandering Rocks notes, and Ithaca

confirms, that he works as an "agent for Pulbrook,

Robertson and Co, 2 Mincing Lane, London, E. C., 5 Dame

street, Dublin)." But the businessman's retreat has not

made "a new man" of Mr. Kernan: his alcoholic habit remains

intact. In Wandering Rocks, he complacently ponders

having just booked a sale with a pub owner by chatting him up

and giving him some business: "I'll just take a thimbleful of

your best gin, Mr Crimmins. A small gin, sir. Yes, sir. . . .

And now, Mr Crimmins, may we have the honour of your custom

again, sir. The cup that cheers but not inebriates, as the old

saying has it."

Nor has Kernan reformed in the second way envisioned by his

friends, by burrowing deep into the bosom of Mother Church. In

Hades he seeks out Bloom, a man who like himself is

nominally Catholic but privately skeptical, to remark that the

priest in Prospect

Cemetery has recited the words of the funeral service

too quickly. Kernan adds that he finds the language of "the

Irish church" (the state-sponsored Protestant religion) to be

"simpler, more impressive I must say." The side-thrusts

continue.

Finally, it also becomes clear that Kernan has experienced no

sudden conversion regarding business ethics. In "Grace," his

wife says she has nothing to offer the gentleman visitors and

offers to "send round to Fogarty's at the corner." Fogarty is

"a modest grocer" whose shop also sells alcoholic beverages,

in the Irish tradition

of the spirit-grocer. "He had failed in business in a

licensed house in the city," because his lack of money kept

him from buying top-drawer products. Later in the story, this

struggling small businessman shows up at the Kernans' house

when Cunningham, Power, and M'Coy are visiting, handsomely

bringing with him "a half-pint of special whiskey" to console

Mr. Kernan on his accident. We learn that "Mr Kernan

appreciated the gift all the more since he was aware that

there was a small account for groceries unsettled between him

and Mr Fogarty."

In Hades, Mr. Power says, "I wonder how is our

friend Fogarty getting on." "Better ask Tom Kernan,"

says Mr. Dedalus. "How is that?" Martin Cunningham asks. "Left

him weeping, I suppose?" "Though lost to sight," Simon

replies, "to memory dear." Mr. Kernan, in other words, has

continued not paying the grocer what he owes him, and is now

so far in arrears that he stealthily avoids meeting him. This

detail of Kernan's shabby financial dealings, together with

his unreformed drinking and his unchanged religious loyalties,

bears out what Mrs. Kernan thinks in "Grace": "After a quarter

of a century of married life she had very few illusions left.

Religion for her was a habit and she suspected that a man of

her husband's age would not change greatly before death."

One final detail carries over from the story to the novel,

subtly suggesting the salesman's slow alcoholic decline from

respectability. "Grace" notes his reliance on a good

appearance: "Mr Kernan was a commercial traveller of the old

school which believed in the dignity of its calling. He had

never been seen in the city without a silk hat of some decency

and a pair of gaiters. By grace of these two articles of

clothing, he said, a man could always pass muster." In Ulysses

he is still banking on this saving "grace," though one

detail suggests it may be wearing thin. After leaving Mr.

Crimmins' establishment, he stands looking at himself in a

mirror, thinking complacently of the favorable effect his

frockcoat had on the bar owner. It is a "Stylish coat, beyond

a doubt," which the tailor, "Scott of Dawson street," could

not have sold for "under three guineas."

Kernan thinks it was "Well worth the half sovereign I gave Neary for

it. . . . Some Kildare street

club toff had it probably. . . . Must dress the

character for those fellows. Knight of the road. Gentleman."

Kernan feels satisfied that he is still dressing up to the

standards of his profession, but he is doing it with

second-hand clothes.

In a letter to his friend Constantine

Curran, Joyce mentioned "My father's old friend R. J.

Thornton ('Tom Kernan')." Vivien Igoe affirms that Joyce

modeled Kernan principally on this man who was godfather to

two of the Joyce children, and who worked as a tea taster and

traveling salesman for Pullbrook, Robertson, & Co. She

reports that Stanislaus described Thornton as "an amusing,

robust, florid little elderly man," and that he died in 1903

in "a tenement building" on Upper Mercer Street. This squalid

ending reads like an echo of Mrs. Kernan's words in the short

story: "We were waiting for him to come home with the money.

He never seems to think he has a home at all."