At the turn of the century the "Kildare street club" was

Dublin's most exclusive men's club, catering to the

Anglo-Irish gentry in a striking building just south of

Trinity College. Dress was important: Bloom thinks in Circe

of a "Kildare street club toff," and Tom Kernan proudly

supposes that his splendid

second-hand topcoat may once have turned heads there:

"Some Kildare street club toff had it probably." ("Toff,"

according to the OED, is "An appellation given by the

lower classes to a person who is stylishly dressed or who has

a smart appearance; a swell; hence, one of the well-to-do, a

'nob'.")

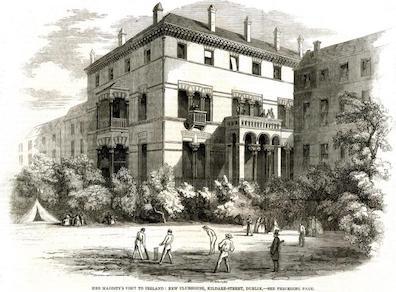

Founded in 1782 for males of the Ascendancy class, the Club

originally occupied a house on Kildare Street, and then two

houses, but by the 1850s it was doing so well that more space

was needed, and three houses on Kildare and Leinster Streets

were demolished to make space for a grand new L-shaped

structure. This new building, designed by Benjamin Woodward

and Thomas Newenham Deane, the architect who designed the National Library and

National Museum, opened in 1860. It featured highly

distinctive arched windows with pairs of slender columns

between them, and "whimsical beasts" carved around the bases

of the columns. These animals are often said to have been

carved by the O'Shea brothers, but Robert Nicholson attributes

the work to C. W. Harrison (Ulysses Guide, 176).

Perhaps the animals were playing in George Moore's

mind when he composed an unforgettable portrait of the club in

the first chapter of Parnell and His Island (1877):

The Kildare Street Club is one of the most important

institutions in Dublin. It represents in the most complete

acceptation of the word the rent party in Ireland; better

still, it represents all that is respectable, that is to say,

those who are gifted with an oyster-like capacity for

understanding this one thing: that they should continue to get

fat in the bed in which they were born. This club is a sort of

oyster-bed into which all the eldest sons of the landed gentry

fall as a matter of course. There they remain spending their

days, drinking sherry and cursing Gladstone in a sort of

dialect, a dead language which the larva-like stupidity of the

club has preserved. The green banners of the League are

passing, the cries of a new Ireland awaken the dormant air,

the oysters rush to their window—they stand there

open-mouthed, real pantomime oysters, and from the corner of

Frederick Street a group of young girls watch them in silent

admiration.

The Club had its own cricket ground, billiard rooms,

card-playing rooms, reading rooms, and drinking rooms. In his

notes for

Dubliners and

A Portrait of the Artist,

Gifford quotes one member to the effect that it was "the only

place in Ireland where one can enjoy decent caviar."

Independence in 1922 spelled the end of the club's growth and

the beginning of its slow decline. It eventually merged with

the Dublin University Club and moved to new premises on the

north side of St. Stephen's Green. The building on Kildare

Street still stands, but it is now used by other

organizations, particularly the Alliance Française.