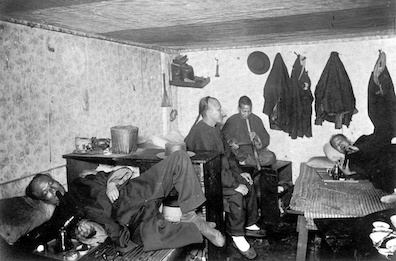

The stereotype of Chinese opium addicts was no fantasy: opium

use was widespread in China and also in Chinese communities

abroad. It was an affliction created and sustained by the

trade policies of the British government and the British East

India Company, who exported opium from their Indian

possessions to China in exchange for tea and other Chinese

goods. The trade was not optional: Britain fought and won two

so-called Opium Wars in 1839-42 and 1856-60 to force China to

keep ports like Canton (Guangzhou), Hong Kong, and Shanghai

open to its merchant ships. As a consequence of this enforced

trade, millions of Chinese became addicted to opium. (So did

many British and French when opium dens sprang up in the home

countries of the colonial powers responsible for keeping China

in subjection.) Bloom imagines that missionaries trying to

sell the Chinese on Christianity may find that their spiritual

needs are already met: "Prefer an ounce of opium."

The fact that he thinks of opium as competition for Christianity

speaks volumes about his view of the religion. As soon as he

enters the church he observes women kneeling "

in the benches

with crimson halters round their necks. A batch

knelt at the altarrails." The words "halters" and

"batch" suggest that these women waiting to receive Communion

are bovine or sheeplike—an impersonal mass of blind believers.

Bloom's critique becomes more overt when the priest who is

slipping wafers into the women's open mouths intones a sacred

formula: "

Good idea the Latin. Stupefies them first." The

people that he sees shuffling back to their pews express no

human emotions: "

He stood aside watching their blind masks

pass down the aisle." And yet, Bloom thinks, something

very pleasurable must be going on inside them: "

Look at them.

Now I bet it makes them feel happy. Lollipop. It does." A

sleepy analgesic haze suffuses the entire church, as in an opium

den: "

Old fellow asleep near that confessionbox. Hence those

snores. Blind faith. Safe in the arms of kingdom come. Lulls

all pain. Wake this time next year."

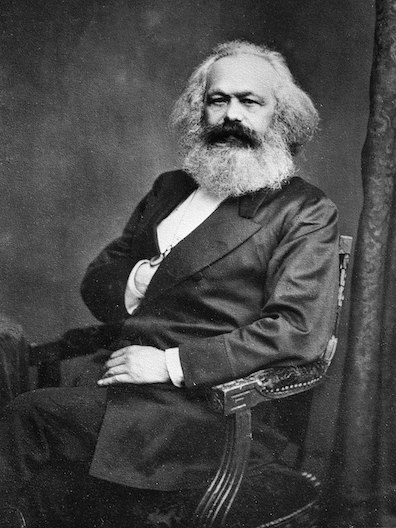

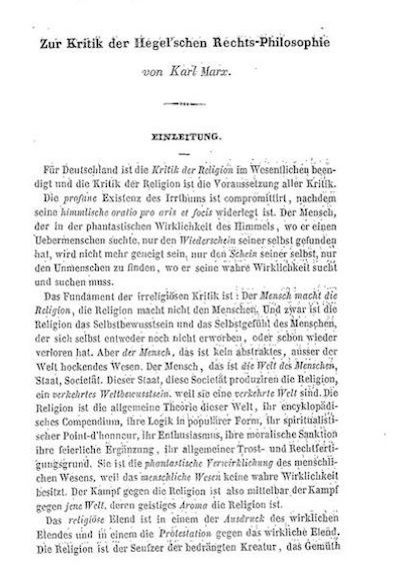

Karl Marx called religion "the opium of the people" in the

introduction to an unpublished 1843 manuscript titled

Critique of Hegel's Philosophy of Right. He used the

word Volk rather than the demeaning language usually

attributed to him ("masses"), and his comments were more

sympathetic to religion than is commonly supposed:

Man is the world of man—state, society. This

state and this society produce religion, which is an inverted

consciousness of the world, because they are an inverted

world.... Religious suffering is, at one and the same time,

the expression of real suffering and a protest against real

suffering. Religion is the sigh of the oppressed creature, the

heart of a heartless world, and the soul of soulless

conditions. It is the opium of the people…. The

abolition of religion as the illusory happiness of the people

is the demand for their real happiness.

(trans. Joseph O'Malley)

Marx cannot have meant the drug comparison to sound simply

hostile and insulting: opium use was perfectly legal in 1843,

and not just common people leading tedious lives but many

leading European artists and intellectuals found solace in it.

He envisions a world in which people will not need either

mood-altering substances or otherworldly consolations to

distract them from the manifest insufficiency of their

existence. Such pleasures are "illusory," but in the world as

presently constituted they are also necessary.

Bloom's ambivalent responses to the worshipers in the church

invite sustained comparison with these views.

Seen objectively, the people in

St. Andrew's may resemble the dazed and dehumanized inhabitants

of an opium den, but Bloom makes an effort to sympathetically

imagine the consolations that their faith provides: "Now I bet

it makes them feel happy. Lollipop. It does.

Yes, bread of

angels it's called. There's a big idea behind it, kind of

kingdom of God is within you feel....

feel all like

one family party, same in the theatre, all in the same swim.

They do. I'm sure of that. Not so lonely. In our confraternity….

Thing is if you really believe in it."

Two annotators of

Ulysses, Kiberd and Slote, cite Marx

as a possible analogue or source for Bloom's "ounce of opium,"

but Thornton, Gifford, and Johnson do not. Both decisions are

defensible. It seems likely that most readers of the novel have

thought of Marx when they see opium mentioned in connection with

religion, but Joyce does not explicitly assert any resemblance

or equivalence. There is also the question of how he could have

known the expression. Marx published his introduction to the

Critique

in 1844, and in the same year he used it also in a piece for an

obscure radical magazine, but these publications were not widely

read. Not until the heyday of international Communism in the

1930s did "the opiate of the masses" become a popular meme.

Skeptics may ask whether Joyce could possibly have read or heard

of it.

Long odds notwithstanding, it is seldom a good idea to bet

against Joyce's nose for obscure, telling details, and this

detail feels almost too perfect to discount. In a chapter

modeled on the Homeric story

of a psychotropic plant that makes life feel bearable

but distracts people from reality, Bloom compares a

psychotropic plant that does the same thing with a religion

that is competing with it. And Marx is mentioned later in Ulysses.

In Cyclops, Bloom shouts out his name as someone whose

work he is proud of: "Mendelssohn was a jew and Karl Marx

and Mercadante and Spinoza. And the Saviour was a jew and

his father was a jew. Your God." Alas for

less-than-totally-obsessive readers of this novel, it is all

too characteristic of Joyce to signal in one chapter the

importance of an author whose ideas are explored in a

different chapter.