Standing in the pharmacy, Bloom thinks that taking a bath

before his 11:00 appointment will fortify his mood: "Feel

fresh then all day. Funeral be rather glum." He picks up a

cake of soap, inhales its lemony aroma, buys it (payment to be

made later), and strolls out of the shop only to run

immediately into a walking refutation of cleanliness in the

person of Bantam Lyons: "yellow blacknailed fingers," "rough

dirt" everywhere, "Dandruff on his shoulders." Bloom thinks of

the ad for Pears' soap, and when he finally gets free of Lyons

he folds the soap carefully in his newspaper and walks toward

the baths, imagining soothing warm water "oiled by scented

melting soap."

These paragraphs at the end of Lotus Eaters portray a

man who values the power of cleanliness to stave off the daily

miseries of life: dirty people shuffling around a dirty city,

moral indifference and personal neglect, the depressing

reality of death and loss. Much later in the novel, Joyce

repeats the scene with some variations as Bloom returns home.

Welcoming Stephen to Eccles Street, he sets a kettle on the

fire to boil water for cocoa and returns to the tap "To

wash his soiled hands with a partially consumed tablet of

Barrington's lemonflavoured soap, to which paper still

adhered (bought thirteen hours previously for fourpence and

still unpaid for), in fresh cold neverchanging everchanging

water and dry them, face and hands, in a long redbordered

holland cloth passed over a wooden revolving roller."

There is an air of ritual in Bloom's washing the dirt of

Dublin off his body both before and after his long trek, and

on both occasions Joyce heightens the effect by providing a

foil to his protagonist's cleanliness. Apparently Bloom offers

Stephen a chance to join him in washing up, because Stephen

gives a reason for declining: "That he was hydrophobe, hating

partial contact by immersion or total by submersion in cold

water (his last bath having taken place in the month of

October of the preceding year)." Bloom is tempted to give his

filthy guest some "counsels of hygiene and prophylactic,"

along with some obsessive-compulsive

tips for bathing ("a preliminary wetting of the head and

contraction of the muscles with rapid splashing of the face

and neck and thoracic and epigastric region in case of sea or

river bathing"), but he wisely bites his tongue to preserve

the spirit of comity that he has only recently achieved with

Stephen.

Together these scenes characterize soap as a kind of

protector of personal integrity, guarding the boundary between

the pristine self and the dirty world outside it. Joyce

suggests its psychological power even more strikingly at the

end of Lestrygonians as Bloom desperately tries to

avoid running into Blazes Boylan in the street. Heart racing

and breath fluttering, he heads for the gate of the National

Museum while frantically searching his pockets, taking strange

comfort in what he at last finds there:

His hasty hand went quick

into a pocket, took out, read unfolded Agendath Netaim. Where

did I?

Busy looking for.

He thrust back quickly

Agendath.

Afternoon she said.

I am looking for that. Yes,

that. Try all pockets. Handker. Freeman. Where did I? Ah, yes.

Trousers. Purse.

Potato. Where

did I?

Hurry. Walk quietly. Moment

more. My heart.

His hand looking for the where

did I put found in his hip pocket soap lotion have to call

tepid paper stuck. Ah, soap there! Yes. Gate.

Safe!

Bloom's searching of his pockets is no doubt

a show calculated to account for

his not looking up and risking eye contact with Boylan before he

gets safely through the museum gate. But the panic is real, and

the text's suggestion that he triumphantly discovers the thing

he is looking for—"

Ah, soap there! Yes"—creates the

impression that the soap is as much his savior as the gate is.

Against what feels like a mortal threat ("My heart"), Bloom

takes comfort in the nugget of sweet-smelling cleanliness that

he carries in his pocket. In

Hades, perhaps

coincidentally, he notices the soap––"

Ah, that soap: in

my hip pocket. Better shift it out of that"––just after thinking

distastefully that the laying out of corpses is an "Unclean

job."

His fetishistic attachment to soap might seem to call for some

kind of psychoanalytic explanation, but what

Ulysses

gives its readers instead are hints of the power of late 19th

century commodity advertising. Explored as a cultural studies

phenomenon in Thomas Richards' book

The Commodity Culture of

Victorian England: Advertising and Spectacle, 1851-1914 (1990)

and Anne McClintock's

Imperial Leather: Race, Gender, and

Sexuality in the Colonial Conquest (1995), soap ads were

brought into Joyce studies by Hye Ryoung Kil in an article

titled "Soap Advertisements and

Ulysses: The Brooke's

Monkey Brand Ad and the Capital Couple,"

JJQ 47.3

(2010): 417-26. These three works provide some highly suggestive

context for Bloom's strong attachment.

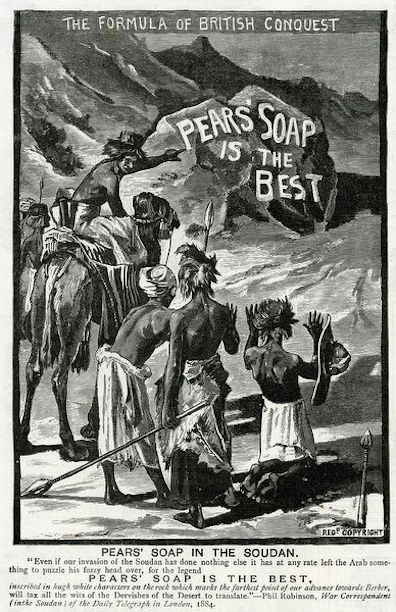

In the second half of the 19th century toilet soap, previously

the privilege of the rich, began to be mass-produced and

marketed to middle-class consumers who appreciated its ability

to differentiate them from the grimy working classes. Starting

in 1884, a brand called Pears' Soap began touting its product in

ads that aligned personal cleanliness not only with freedom from

manual labor but also with superiority to the dark-skinned

laborers in Britain's colonies. Omnipresent print ads promised

to lift users of their soap into the ruling class, asking, "

Good

morning! Have you used Pears' Soap?"

So pervasive was this advertising that, according to a book by

James B. Twitchell cited in one of Kil's endnotes, well-bred

Victorians became leery of saying "good morning" to one another,

lest they seem to be repeating the language of the ads. Bloom,

however, does not sound very embarrassed when he imagines

spouting the line to the filthy Bantam Lyons. He evidently

thinks that the man should improve himself.

It is hard to know just how much purchase the ad may have on

Bloom's thinking. He is an advertising man, after all, and

jingles and pitches pass through his mind all day without

necessarily saying much about his beliefs. But the novel does

provide plenty of hints about how the British ideal of

cleanliness embodied in the soap ads might appeal to a man in

Bloom's social station. The British had long sought to suggest

that the white people they colonized on the island next door

were somehow racially different from themselves, presenting the

Irish in countless cartoons as dirty, hairy, negroid ape-men.

And Bloom, of course, has an additional racial hurdle to

surmount: he struggles even to be accepted as legitimately

Irish. In

Cyclops the Citizen calls him a "

whiteeyed kaffir,"

demeaning him by association with Africans just as the English

did with the Irish.

The sense of racial inferiority that Bloom struggles with can be

seen in the language that he uses in

Lestrygonians to

characterize Reuben J. Dodd, a man whom he takes to be Jewish

but less successful at integrating himself into Gentile society:

"

Now he’s really what they call a dirty jew." His love of

hygeine may well contain an element of

servile aspiration. The Pears

ads, without doubt, encouraged and justified such aspiration. As

Kil observes, "The possibility of racial cleansing and the

progress of the dominated depicted in soap ads subversively

challenged the idea that cleanliness was uniquely English....

the virtuousness of white civilization appeared to be a cultural

rather than a natural attribute that anyone could purchase"

(418).

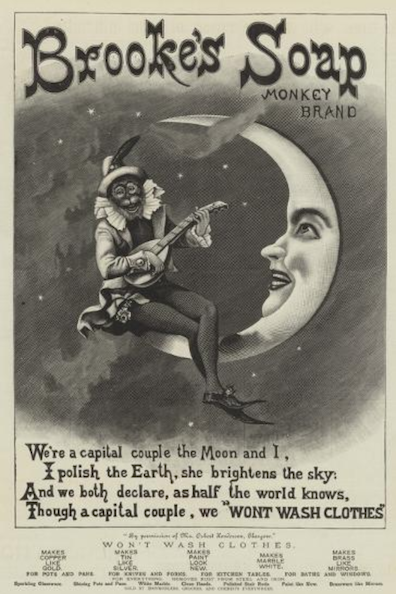

The ad parodied in

Circe was for a different kind of

soap, one used for cleaning household surfaces rather than the

human body. "Brooke's Soap Monkey Brand," manufactured by an

American company, was advertised in 1891 in an image that showed

a minstrel-like monkey sitting on the tip of the crescent moon

and singing, "

We're a capital couple the Moon and I, / I

polish the earth, she brightens the sky." Only this one ad

used the conceit of the moon, but many others featured the

dressed-up monkey. Its resemblance to 19th century depictions of

Irishmen and Blacks is probably not accidental. Kil suggests

that the monkey stood in for all those people (manual laborers,

women, colonial subjects) on whose backs empire was built and

households cleaned, while simultaneously suggesting that the

soap had magically rendered brute labor unnecessary.

By substituting Bloom for this half-civilized simian, the novel

may be portraying its protagonist as an Irish-Jewish mongrel who

believes that the right kind of soap can confer a kind of racial

purity. But the Monkey Brand ads appeared to target class and

gender as much as race: they evoked a world in which household

cleaning was accomplished by the magic of modern chemistry

rather than by the arms of

charwomen.

This distancing of consciousness from the labor of domestic help

has a presence in

Circe. Twenty pages after the parody

of the Brooke's ad, a woman who performed menial physical labor

in Bloom's home, Mary Driscoll, accuses him of having

propositioned her, and he uses racially suggestive language to

refute her: "

I treated you white. I gave you mementos,

smart emerald garters far above your station. Incautiously I

took your part when you were accused of pilfering." Mary here is

the monkey in the house, magically ennobled and effaced by the

kind of thinking that polishes the earth and brightens the sky.

Kil's article raises another line of questioning whose

implications are very murky, but probably worth mentioning. In

1899 the British firm Lever Brothers bought Brooke's Soap

after noting its effectiveness in selling household soap,

which British manufacturers had not previously bothered to

advertise. In British hands the ads for Monkey Brand came to

more closely resemble the Pears ads promising to civilize the

dusky world. Did Joyce view the two soaps through the same

colonialist lens? This seems possible, but Kil also suggests

that he may have felt more sympathetic toward the company that

produced the 1891 ad because it was American. The soap that

Bloom carries around all day is Irish, and in Lestrygonians

he thinks happily of giving Milly baths with an "American

soap I bought: elderflower." When the Irish soap

diffuses light and perfume about the sky and proclaims in an

American spirit that "We're a capital couple are Bloom and

I," could it possibly be evoking independence from

colonial domination rather than submission to it? This is one

of several tantalizing questions raised, but hardly answered,

by the novel's engagement with soap ads.