In addition to the overlay of fictive underworlds created by

allusions to the epic poems of Homer,

Virgil, and Dante, Hades

also draws upon the quite realistic, this-worldly graveyard of

Shakespeare's Hamlet. The previous chapter has shown

that Bloom knows this work, well

enough even to quote from it, and in Hades

he thinks five or six times of the play's countless references

to dead bodies. Several of these thoughts have to do with

putting corpses into the ground, and the need to maintain a

sense of humor about the grim business.

Sitting in the carriage outside Dignam's house Bloom ponders

women's work of laying out men's corpses, a job performed "Huggermugger

in corners." This word, which the OED

traces back to the early 16th century, refers to secrecy or

concealment, and in Hamlet it is applied to the

attempt to conceal Polonius' death. After stabbing him, Hamlet

rudely drags his corpse offstage to hide it: "This man shall

set me packing; / I'll lug the guts into the neighbor room"

(3.4.211-12). Then, after Claudius gets him to say where he

stashed the body––"if you find him not within this

month, you shall nose him as you go up the stairs into

the lobby" (4.3.35-37)––the king too hides it, ordering that

it be buried secretly. He soon has reason to regret the shady

dealing, as he confesses to Gertrude: "we have done but

greenly / In hugger-mugger to inter him"

(4.5.83-84).

Bloom no doubt recalls these lines because the thought of

concealing bodies "in corners" confirms his sense of the human

need to hide the ugly fact of death: "Plant him and have done

with him. Like down a coalshoot." He is probably also tickled

by the comical sound of "huggermugger," so similar to "slipperslappers" in the

next sentence, because the entire chapter shows him responding

flippantly to funereal solemnity. Later, when he is walking

through the cemetery, he thinks of both the gruesomeness and

the comedy of burial, in successive paragraphs that recall the

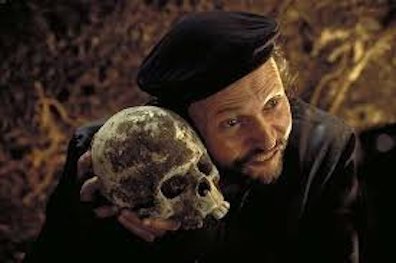

graveyard scene in Hamlet.

The first of these paragraphs consists of Bloom's grisly

thoughts about decomposition:

I daresay the soil would be quite fat with

corpsemanure, bones, flesh, nails. Charnelhouses. Dreadful.

Turning green and pink decomposing. Rot quick in damp earth. The

lean old ones tougher. Then a kind of a tallowy kind of

a cheesy. Then begin to get black, treacle oozing out of them.

Then dried up.

It is hard not to hear in this entire meditation, as Thornton

does in the sentence about "lean old ones" being tougher, an

echo of the gravedigger's answer to Hamlet's question, "How long

will a man lie i' th' earth ere he rot?" (5.1.163-64). It

depends, says the gravedigger: "we have many pocky corses, that

will scarce hold the laying in" (166-67). At the opposite

extreme from these pre-rotted corpses are the bodies of tanners,

which may last eight or nine years: "his hide is so tann'd with

his trade that 'a will keep out water a great while, and your

water is a sore decayer of your whoreson dead body" (170-72).

In the following paragraph Bloom thinks that despite all this

horror the caretaker comes to work with a smile:

He looks cheerful enough over it. Gives him a sense

of power seeing all the others go under first. Wonder how he

looks at life. Cracking his jokes too: warms the cockles of

his heart. The one about the bulletin. Spurgeon went to heaven

4 a.m. this morning. 11 p.m. (closing time). Not arrived yet.

Peter. The dead themselves the men anyhow would like to hear

an odd joke or the women to know what's in fashion. A juicy

pear or ladies' punch, hot, strong and sweet. Keep out the

damp. You must laugh sometimes so better do it that way.

Gravediggers in Hamlet. Shows the

profound knowledge of the human heart. Daren't joke

about the dead for two years at least.

Social mores may prescribe a respectful period of not joking

about the dead, but O'Connell jokes about heaven having closing

time like a pub before the holes are even filled. Bloom is quite

right to hear in this an echo of

Hamlet's gravediggers.

As they dig a hole for Ophelia the clever one jokes about

suicide ("he that is not guilty of his own death shortens not

his own life"), the nobility of gardeners and diggers (clearly

Adam "bore arms": "could he dig without arms?"), and the riddle

of who builds the strongest structures (the gravedigger: "the

houses he makes lasts till doomsday"). He gets the best comic

line of the scene when Hamlet asks about the grave he is

digging. What man is it for? No man. What woman? No woman. Then

for whom? "One that was a woman, sir, but, rest her soul, she's

dead" (135-36).

Hamlet does not yet know that Ophelia has drowned herself and is being

buried without full Christian rites, so the humor is quickly

followed by anguish. This may perhaps show the "profound

knowledge of the human heart" that Victorians supposed

Shakespeare to possess. It certainly does show his remarkable

ability to leaven tragedy with comedy. In Elsinore's graveyard

and at the gates of Macbeth's castle, "suffering takes place,"

as Auden writes in Musée des Beaux Arts, "While

someone else is eating or opening a window or just walking

dully along." Life goes on, and to the extent one can make

light of its insupportable griefs, one should. As Bloom says,

"You must laugh sometimes."