"DEAR DIRTY DUBLIN" is often attributed to Sydney

Owenson, Lady Morgan (ca. 1781-1859), an Irish socialite and

writer best known for The Wild Irish Girl (1806). In a

survey of sources of the expression on JJON, John

Simpson notes that evidence shows "it arose within Lady

Morgan’s circle or comparable aristocratic circles in Britain,

but does not confirm that Lady Morgan is herself responsible

for it." Linguistic precursors ("Dear, dirty...Scotland,"

"dear Dublin," "dirty Dublin," "dear, droll, dirty Fabulist,"

"dear little Dublin," "dear little Ireland") extend far back

into the 18th century, and in the 1820s similar phrases

(including the "dear dirty" pairing) circulated in Lady

Morgan's upper-class circles. In her Memoirs she wrote

that she returned to "our own dear but dirty little home" in

Dublin in 1829 after traveling abroad. In the 1830s, the "dear

dirty" pairing of adjectives gained wide currency and was

sometimes applied to Dublin. In the 1840s and 50s "dear, dirty

Dublin" became a common expression.

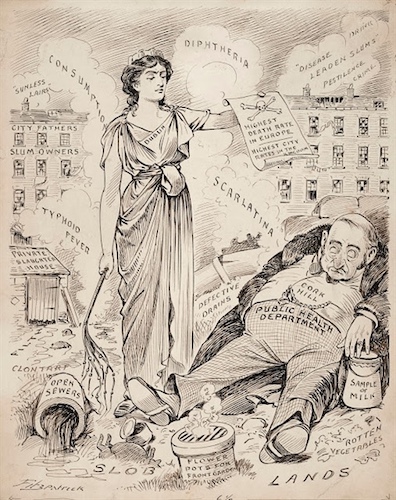

Finally the origins of the phrase are less important than the

ambivalence conveyed in it. In her Memoirs Lady

Morgan called Dublin "unfortunate," "a dreary desert occupied

only by loathsome beggars," the "Wretched" capital of

"wretched Ireland." She loved her native city but found its

poverty and filth revolting. This mix of attitudes is

maintained in Aeolus. The newspaper-like headline

conveys a syrupy tone of sentimental tenderness toward the

Hibernian metropolis: our dear home may be a bit tawdry, but

we all love it. Stephen's story, however, draws on the dirty

parts. Two over-the-hill, overweight, and half-infirm women

from a really dismal area in the Liberties trudge into the

commercial heart of Dublin, buy some cheap food, shell out

some hard-earned pennies for admission to Nelson's imperial

monument, wheeze their way up the 168 stone stairs inside

while piously invoking God and the Blessed Virgin, and

collapse on the viewing platform, dribbling plum juice from

the corners of their mouths and spitting seeds onto the street

below while evidently entertaining some sexual fantasies in

the presence of "the onehandled adulterer."

There is nothing particularly "dear" about this portrait.

James Joyce took his first small step toward epic artistic

accomplishment when he began recording little vignettes of

Dublin life that he called epiphanies or epicleti. The

religious language did not imply a Symbolist transformation of

ordinary experience. It indicated only flashes of revelatory

insight into the perfectly ordinary human realities that

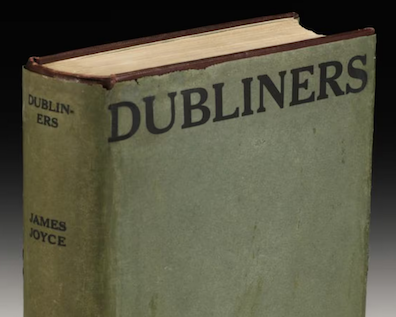

interested Joyce. By 1906 he had expanded these little

glimpses of mundane human life into the stories he called "Dubliners"––one

of the greatest short story collections ever––and the

manuscript was accepted for publication by London publisher

Grant Richards. But Richards got cold feet and did not consent

to publish the stories until 1914. Joyce's letter of protest

to the weak-kneed Richards suggests that the miserable

tawdriness of "dirty Dublin" was at the heart of the

standoff:

It is not my fault that the odour of ashpits

and old weeds and offal hangs round my

stories. I seriously believe that you will retard the course

of civilisation in Ireland by preventing the Irish people from

having one good look at themselves in my nicely-polished looking-glass.

Dubliners paints a series of portraits of people

fatally mired in dead-end lives, paralyzed by poverty, piety,

sexism, alcoholism, colonialism, romanticism, asceticism, and

general inertia. Stephen's story of the two aged virgins is a

little more cheerful, but it does not feel out of place among

these bleak pictures of human futility. Indeed, it seems to be

partly informed by the reminiscence of another couple he saw

walking on the beach in Proteus, a gypsy woman and her

pimp plying their dismal trade in the same Blackpitts area

where Stephen places the two old women's home: "Damp night

reeking of hungry dough. Against the wall. Face glistening

tallow under her fustian shawl. Frantic hearts." His

willingness to try out these epiphanic scene-paintings as a

pathway to fictional creation ("On now. Dare it. Let there

be life") suggests that he is ready to leave behind his

fairly sterile

career as a poet and turn toward the writing of prose

fiction.

In Joyce's case this led to the writing of Dubliners,

and perhaps Stephen will eventually write some stories

himself. But what readers get in his little Parable

of the Plums is equally evocative of the methods

of the great novel that came next. Ulysses contains

all the bleak realities and ruined lives found in Dubliners,

but it shows them through the lenses of choice, possibility,

affirmation, and hope. It is a book of what the Professor

calls "prophetic vision": Stephen may become the artist

he aspires to be, the Blooms may find happiness in their

marriage, dark horses may win life's races, and Ireland may

find liberation from England. (This last prophetic prediction

proved true in 1922, the same year the novel was published.)

Stephen thinks, "I have a vision too," and if his tale

contains one it is to be found at the end, when the two women

behave in a sexually suggestive manner sprawled on their

petticoats looking up at the statue of the English conqueror.

This is truly parabolic––strange,

obscure, as resistant to easy interpretation as the most

baffling of Jesus's tales. But when the two women "lift up their

skirts" to Lord Nelson, one distinct possibility is that

readers should see them symbolically defying the British

empire by casting an apotropaic spell on its representative.

This kind of symbolism––perhaps not even remotely available to

the consciousness of the ordinary people walking the streets

of Dublin, but integral to the greater organization of the

book that gives them life––is all too typical of Ulysses.

If Stephen intends it, then he shows himself already capable

of writing a book greater than Dubliners. But first he

has "much, much to learn" about the city that can

provide a canvas for such cosmographic generation of meaning.