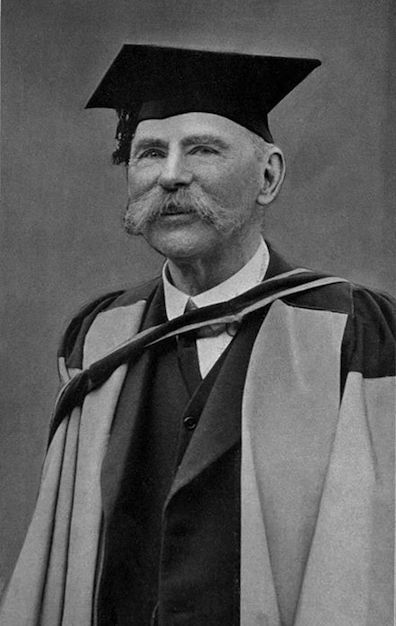

Douglas Hyde (1860-1949), known also as An Craoibhín Aoibhinn

(the Sweet Little Branch or Pleasant Little Branch), was an

important scholar of the Irish language who played a major

part in the Irish Cultural Revival.

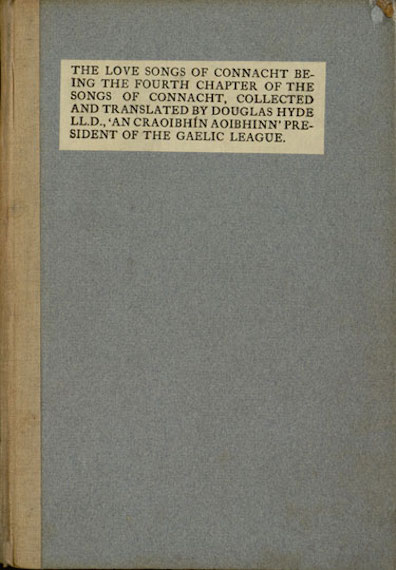

His popular Love Songs of Connacht (1893) published

Irish poems that he had collected in the West, with verse and

prose translations into English. Haines misses Stephen's talk

in the library because he has gone to buy a copy of Hyde's

book. To add injury to insult, the novel marks Stephen's

failure (so far) to distinguish himself as a poet by having

him shape sounds—"mouth to her mouth's kiss"—that

clearly derive from one of Hyde's lyrics.

In Scylla and Charybdis Mr. Best announces that "Haines is gone." The Englishman

had expressed interest in

hearing Stephen's talk on Shakespeare, but Best's mentions of

Irish mythology and poetry have sent him off in a different

direction: "He's quite enthusiastic, don't you know,

about Hyde's Lovesongs of Connacht. I

couldn't bring him in to hear the discussion. He's gone to

Gill's to buy it." John Eglinton comments

sardonically on this quest for Irish authenticity: "The

peatsmoke is going to his head." But George Russell voices the

ambitions of the Revival: "— People do not know

how dangerous lovesongs can be, the auric egg of

Russell warned occultly. The movements which work revolutions

in the world are born out of the dreams and visions in a

peasant's heart on the hillside." In Wandering Rocks

we encounter Haines sitting at the DBC with "his

newbought book."

The repetitive motif at the heart of Stephen's poetic

manipulations of sound in Proteus—"mouth to

her mouth's kiss. . . . Mouth to her kiss. No. Must

be two of em. Glue em well. Mouth to her mouth's

kiss. / His lips lipped and mouthed fleshless lips of air:

mouth to her womb. Oomb, allwombing tomb"—comes from

the last stanza of "My Grief on the Sea," a poem in Hyde's Love

Songs:

And my love came behind me—

He came from the South;

His breast to my bosom,

His mouth to my mouth.

Stephen has ambitions to transform the simple verses into

something grandiose and gothic—"He comes, pale vampire, through storm his

eyes, his bat sails bloodying the sea, mouth to her

mouth's kiss"—but he has not yet achieved

even that dubious transformation of a minor lyric.

Cyclops has fun with the kind of literary recovery

projects that Hyde undertook, paying serious scholarly

attention to the canine verse of Garryowen: "Our

greatest living phonetic expert (wild horses shall not drag

it from us!) has left no stone unturned in his

efforts to delucidate and compare the verse recited and has

found it bears a striking resemblance (the italics

are ours) to the ranns of ancient Celtic bards. We

are not speaking so much of those delightful lovesongs with

which the writer who conceals his identity under the

graceful pseudonym of the Little Sweet Branch has

familiarised the bookloving world but rather (as a

contributor D. O. C. points out in an interesting

communication published by an evening contemporary) of the

harsher and more personal note which is found in the satirical

effusions of the famous Raftery and of Donal MacConsidine to

say nothing of a more modern lyrist at present very much in

the public eye."

Hyde grew up in the west, in Sligo and Roscommon, and learned

Irish from the quarter of the population who still spoke it in

the countryside in those counties. Passionately dedicated to

preventing the extinction of the native language and culture,

he contributed to Yeats’s Fairy

and Folk Tales of the Irish Peasantry (1888),

published his own Besides the Fire: A Collection of Irish

Gaelic Folk Stories in 1890, and, after the Love

Songs in 1893, also published Religious Songs of

Connacht in 1906, as well as scholarly works like

The Story of Early Gaelic Literature (1895) and the Literary

History of Ireland (1899). He collaborated with Yeats

and others in the work of the Literary Theatre, which became

the Abbey Theatre, and he exerted immense cultural influence

through the Gaelic League until that group was infiltrated by

Sinn Féin and became an

essentially political organization. In 1938 he became the

first President of the new Irish republic.

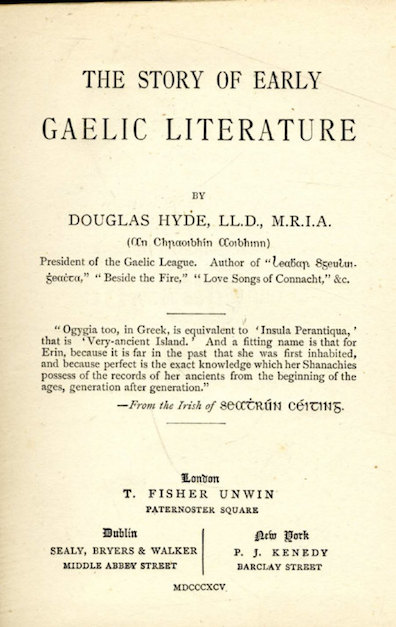

Scylla and Charybdis reproduces nearly verbatim one

of Hyde's quatrains:

Bound thee forth my Booklet quick.

To greet the Polished Public.

Writ—I ween't was not my Wish—

In lean unLovely English.

The six-stanza poem that begins with these lines concludes

Hyde's The Story of Early Gaelic Literature. That

Stephen knows part of it by heart (characteristically, he

makes the Public "callous") suggests that he has some

considerable regard for Hyde's writings.