§ Gifford

observes that "Synge created a [ahem!] singularly poetic and

dramatic language out of the peculiar combination of Irish

syntax and archaic English diction" that he heard spoken in

County Wicklow and the west of Ireland. His one-act play Riders

to the Sea was first performed in Dublin starting in

late February 1904. It is fair to suppose that when Joyce

penned Mulligan's mocking imitation of Irish speech he was

thinking primarily of Riders to the Sea and even

suggesting that Mulligan has attended a Dublin performance of

this play and has its lines ringing in his ears. The narrative

introduces his sentences by saying that he "keened in

a querulous brogue," and the play is all about keening.

Slightly later in Scylla, when Stephen invokes Thomas

Aquinas, Mulligan reprises his mourning ("he keened a

wailing rune") and repeats nearly verbatim what one of

the characters of Riders says as she begins to keen:

"It's destroyed we are from this day! It's destroyed we are

surely!"

Most English-speakers have some awareness of keening as a

high-pitched wailing lamentation for the dead, but they may

not recognize it as an ancient Irish practice or know that the

word is an Anglicization of the Irish verb caoin. Set

on one of the Aran Islands, in the Gaeltacht, Riders to the

Sea stages the story of Maurya, who has lost a husband

and five sons to the sea. Her daughters Cathleen and Nora

receive word that a body which may be that of their brother

Michael has washed up on the coast of Donegal. It does prove

to be Michael, and by the end of the play the sea also claims

Bartley, the one remaining son. All three broken-hearted women

keen their ruinous losses, which may well bring them to the

brink of starvation. By contrast, Mulligan's mournful wailing

is sparked by the fact that Stephen did not show up at the Ship to buy him drinks.

The word "querulous" means "complaining, peevish,

plaintive." One imagines Mulligan adopting one of his

old-woman voices, perhaps some variant of Mother Grogan's, to press

his countrified, wheedling, whining complaint.

§ The

word "brogue" is a familiar name for English spoken

with an Irish accent. But like "keen" it derives from an Irish

word: either bróg = shoe (a word that appears several times in Ulysses)

or barróg = speech defect. Dolan notes a

possible connection between the two, though this etymology is

contested: "There is a view that Irish people used to speak

English unintelligibly (as a result of linguistic

contamination from Irish syntax and vocabulary), and the

effect was as if they had a shoe on their tongue." When Joyce

writes in Finnegans Wake that HCE's "sbrogue cunneth

none lordmade undersiding," he seems to be playing with this

notion that thick-tongued Hiberno-English speech can be hard

to understand.

The brogue that flows from Mulligan's mouth is indeed hard to

understand in many particulars, though its general intention

is clear enough:

It's what I'm telling you,

mister honey, it's queer and sick we were,

Haines and myself, the time himself brought it in. 'Twas

murmur we did for a gallus potion would rouse a friar,

I'm thinking, and he limp with leching. And we one hour and

two hours and three hours in Connery's sitting civil waiting

for pints apiece.

He wailed:

— And we to be there, mavrone,

and you to be unbeknownst sending us your conglomerations the

way we to have our tongues out a yard long like the drouthy

clerics do be fainting for a pussful.

Stephen laughed.

§ The

passage paints a simple comic scene of Mulligan and Haines

sitting in the pub, painfully waiting for Stephen (as Synge's

women wait for news), and receiving only a telegram ("it"). The

syntax and verbal delivery echo Synge's representation of the

Aran islanders' lilting speech. Using a reflexive pronoun as a

subject, for example ("

himself brought it in"), is a

linguistic practice used often in the play ("Herself does be

saying prayers half through the night"), as is the insistent use

of "it" ("If it wasn’t found itself, that wind is raising the

sea, and there was a star up against the moon, and it rising in

the night. If it was a hundred horses, or a thousand horses you

had

itself, what is the price of a thousand horses

against a son where there is one son only?").

"

And we to be there" imitates the islanders' distinctive

use of conjunctions ("How would it be washed up, and we after

looking each day for nine days"). Another such idiom involving

"way" ("the way we can put the one flannel on the other") shows

up in Mulligan's "

the way we to have our tongues out." "

I'm

thinking" too recalls the speech of the play ("I’m

thinking it won't be long," "I'm thinking Bartley put it on him

in the morning"). Even Mulligan's counting of the hours ("

And

we one hour and two hours and three hours") echoes the

islanders' speech ("I’ll have half an hour to go down, and

you’ll see me coming again in two days, or in three days, or

maybe in four days if the wind is bad").

§ More such

echoes could be cited, but this note will highlight just one

other that is heard often in Irish speech. Commenting on the

churchmen that Mulligan says "

do be fainting" for a

drink, Slote cites P. W. Joyce: "In the Irish language (but not

in English) there is what is called the consuetudinal tense,

i.e. denoting habitual action or existence. It is a very

convenient tense, so much so that the Irish, feeling the want of

it in their English, have created one by use of the word

do

with

be: 'I do be at my lessons every evening from 8 to

9 o'clock'."

This kind of verbal construction is not completely absent from

the English spoken in England: there, people sometimes use the

future tense to imply habitual action, saying that boys will be

boys or clerics will be drinking. But the Irish way is much more

vivid. Many examples can be found in Synge's plays, including a

few in

Riders to the Sea: "the black hags that do be

flying on the sea," "In the big world the old people do be

leaving things after them for their sons and children, but in

this place it is the young men do be leaving things behind for

them that do be old." Characters speak in this way at several

other points in

Ulysses. In

Lestrygonians Nosey

Flynn tells the story of a woman who hid in a clock in the

Masons' hall to discover "what they

do be doing," and

Bloom imagines a constable pressing a servant girl with the

question, "And who is the gentleman

does be visiting

there?" In

Wandering Rocks Patsy Dignam thinks of "One

of them mots

that do be in the packets of fags Stoer

smokes."

While the syntactic rhythms of Mulligan's keening are clearly

derived from reading or listening to Synge, the vocabulary is

his own, and it far outdoes Synge for obscurity.

Riders to

the Sea employs no words more unfamiliar than "poteen"

(Irish moonshine) or "Samhain" (a pagan Gaelic fall festival).

Mulligan leads off with "

mister honey," which no

commentator has even directly addressed, much less

satisfactorily explained. In a personal communication, Senan

Molony argues that this must be a playful anglicization of some

Irish phrase. He offers one possibility:

más é do thoil é,

literally "if it is your will," or figuratively "if you please."

Spoken quickly, as this very long way of saying "please" must

be, "mar-shay-duh" would sound quite a bit like "mister,"

"hol-lay" could be twisted into "honey" with the change of one

consonant, and the meaning, "please," might conceivably advance

Mulligan's wheedling entreaty. The fit is admittedly loose, but

Molony's hypothesis is intriguing. Perhaps other Irish language

models will eventually be proposed.

The next two strange expressions appear to comically amplify the

beggars' thirst. Slote cites P. W. Joyce's observation that in

Hiberno-English, "particularly in Ulster, 'Queer and' is an

intensifier." Being "

queer and sick," then, means that

Mulligan and Haines were sick unto dying with thirst. The

OED

identifies "

gallus" as an obsolete form of "gallows."

The suggestion does not seem to be that the two men were longing

for a pint that deserved capital punishment, or for a deadly

one, or for one capable of promoting sexual excitement (Gifford,

responding to the mention of rousing a friar who is "limp with

leching," wildly surmises that the word evokes "the commonplace

that a man being hanged has an erection in the process"). Much

better, though certainly strange enough, is Slote's observation

that "gallows" too can be an intensifier. The

OED lists,

after all its other meanings, this one: "With intensive force:

Extremely, very, 'jolly'." A jolly big alcoholic potion, then.

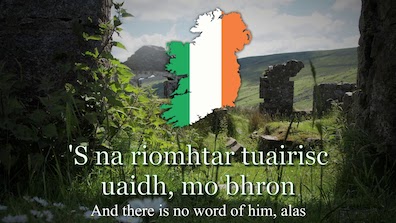

In the next paragraph, "mavrone" is a common

Hiberno-English interjection borrowed from the Irish mo

bhrón, meaning literally "my sorrow" or "my regret."

Mulligan's keening here takes the form of "alas!"—no drinks

after all that time waiting. In "drouthy clerics," he

dips into obscure English once more. This is a Scottish

variant of "droughty," so the basic meaning is "dry, without

moisture, arid," but the OED lists a metaphorical

application: "thirsty; often = addicted to drinking."

Finally, the "pussful" of ale that the good fathers

and brothers do be wanting might possibly refer to their

faces, but more likely it echoes a slang use of "puss" for

"mouth." These meanings cannot be found in most dictionaries

of English written for English people, but The American

Heritage Dictionary, which reflects many usages brought

into American English by Irish immigrants, identifies both

slang uses: "1. The mouth. 2. The face. [Irish bus,

lip, mouth, from Old Irish, lip]." Dolan's Hiberno-English

dictionary translates "puss" only as mouth, and "shaping the

lips so as to make a pout; sulking." It cites a response to

such pouting: "Take that ugly sour puss off your face and get

on with the messages." Slote cites P. W. Joyce's relevant

observation that "puss" is "always used in dialect in an

offensive or contemptuous sense." Churchmen can never catch a

break from Mulligan.