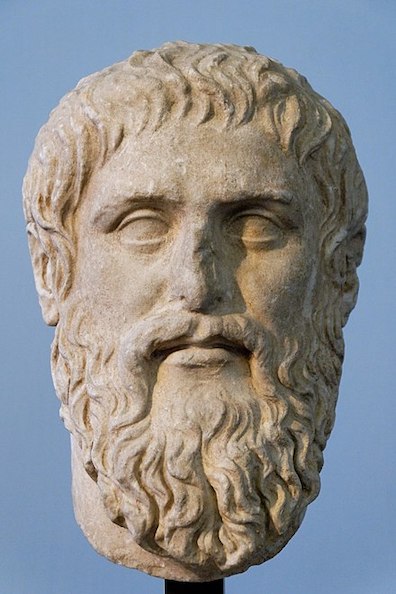

"Plato's world of ideas" is, of course, the realm of

incorporeal constitutive principles that Plato thought to be

more real than the things of sensory experience. He never

describes them as existing in a "world" distinct from this

world, but passages in his works can be read as suggesting

something like that. The Phaedrus speaks of the soul

taking flights to "that place beyond the heavens"––topos

hyperuranios––where "true being dwells," including

"justice, its very self, and likewise temperance, and

knowledge, not the knowledge that is neighbor to becoming and

varies with the various objects to which we commonly ascribe

being, but the veritable knowledge of being that veritably is"

(247c-e, trans. R. Hackforth). The allegory of the cave in the

Republic creates a sense of two worlds by imagining

human beings who are slaves to sensory impressions as

prisoners chained in darkness and watching blurry figures

dance across a wall. To be truly sapient and behold things as

they actually are, the prisoner must free himself and exit the

cave. But this story is a series of metaphors, not a

cosmological description.

Considerably looser echoes of Platonism can be heard in a

favorite phrase of Russell's, "formless spiritual essences."

Gifford quotes a passage from the artist's essay Religion

and Love (1904): "Spirituality is the power of

apprehending formless spiritual essences, of seeing the

eternal in the transitory, and in the things which are seen

the unseen things of which they are the shadow." This sounds

as much Theosophical as Platonic, and there is great irony in

calling the Ideas "formless," because eidos, a term

that Plato uses synonymously and interchangeably with idea,

means "visible form." (The root eido means "to look,"

and the English word "eidetic" refers to mental images that

are so vividly detailed that they seem actually visible.) Eidos

is form, shape, figure––literally, the look of something––and

Plato uses it in much the same way that Aristotle uses a

closely related word for form, morphe. Calling the

Platonic Ideas formless is absurd, then––equivalent to saying

"Forms without form." (Only in the last hundred years have

English translators begun to replace Idea with Form, so

whether Joyce was aware of this irony is open to question.)

In rejecting Russell's freefloating spirituality Stephen is

not exactly disagreeing with Plato. Several paragraphs later

in Scylla, however, the discussion comes closer to

something that the philosopher actually wrote. John Eglinton

listens to Stephen and exclaims, "Upon my word it makes my

blood boil to hear anyone compare Aristotle with Plato."

Stephen replies, "Which of the two...would have

banished me from his commonwealth?" It was Plato who did

this in book 10 of the Republic, arguing that

representational arts like painting and poetry should be

banned in the ideal society because they mistake sensory

reality for truth and excite passions that should be

restrained. Aristotle answered these charges in the Poetics,

arguing that literary fictions represent particular events in

such a way that universal truths can be seen in them, and

arouses passions in such a way as to effect emotional

catharsis.

This debate about the value of art is never discussed in Ulysses,

but it is relevant to Stephen's talk. His deep dive into

Shakespeare's home life expresses a belief that real events

are essential to artistic projects and can beget universal

insights: "He goes back, weary of the

creation he has piled up to hide him from himself, an old dog

licking an old sore. But, because loss is his gain, he passes

on towards eternity in undiminished personality, untaught

by the wisdom he has written or by the laws he has revealed."

Shakespeare's sexual life may have been as messy and uncertain

as any other mortal's, but by writing about it so brilliantly

he revealed "laws" of human psychology. In contrast, Russell

opines that lived experience, with all its richness of

sensation and feeling, has little to do with great art:

"Interesting only to the parish clerk. I mean, we have the

plays. I mean when we read the poetry of King Lear what

is it to us how the poet lived? As for living our servants can

do that for us, Villiers de l'Isle has said. Peeping and

prying into greenroom gossip of the day, the poet's drinking,

the poet's debts. We have King Lear: and it is

immortal."

Russell cites three more examples of such transcendent art: "The

painting of Gustave Moreau is the painting of ideas. The

deepest poetry of Shelley, the words of Hamlet bring our

minds into contact with the eternal wisdom, Plato's world of

ideas." Moreau, a French Symbolist painter of the second half

of the 19th century, was highly esteemed by the fin-de-siècle

aesthetes of the 1890s. His paintings often contain surreal

and even hallucinatory details. The Apparition, shown

here, distances viewers from the familiar biblical tale of

Salome and Herod by representing a dreamlike vision of John

the Baptist's severed head rather than the real thing. Percy

Bysshe Shelley, who wrote about visions of intellectual or

spiritual reality within or behind the visible world, has

often been called the most Platonic of the Romantic poets.

As for Hamlet, Russell presumably is referring to soliloquies

like "To be or not to be" in which the prince reflects on

divine purposes and the afterlife. Stephen retorts that

Aristotle "would find Hamlet's musings about the afterlife of

his princely soul, the improbable, insignificant and

undramatic monologue, as shallow as Plato's." Gifford

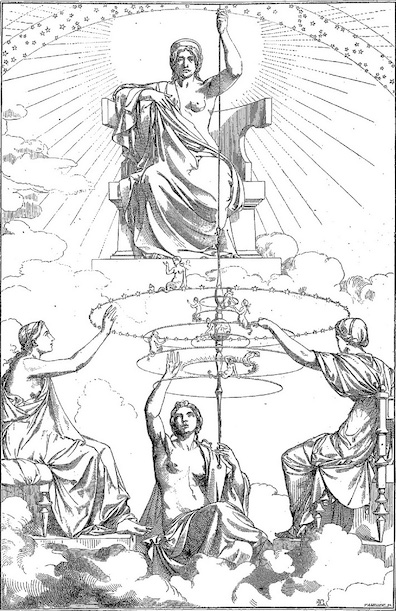

supposes that the Platonic reference here may be to the myth

of Er at the end of the Republic, which represents

dead souls deciding what forms to take in their next reincarnations.

Like Hamlet, who asks whether death will free him of "the

thousand natural shocks / That flesh is heir to," Odysseus is

represented in Plato's myth as seeking a humble new life in

which he will be free of "cares."

Aristotle did not believe in a personal afterlife. In De

Anima 3.5 he argues that human thinking ceases when the

body dies. All that survives death is the "active" force in

intellection, which is incorporeal, immortal, and outside of

time, "a sort of positive state like light." This entity acts

upon corporeal faculties to produce thought but it is in no

way contained within them. It strongly resembles God, the

"unmoved mover," as Aristotle describes that impersonal entity

in the Metaphysics.