In response to Russell's declaration of Platonic

aesthetics early in Scylla and Charybdis,

Stephen declares himself a follower of Aristotle and ticks

through a checklist of things he knows about that philosopher:

his having studied under Plato, his founding of a rival

philosophical school, his generally more empirical approach,

his disagreement about the nature of the Forms, his defense of

representational art, his examination of the senses, and his

influence on the Scholastic philosophers. These thoughts

strengthen Stephen's resolve "Hold to the now, the here"

instead of pursuing transcendent spirituality. Punning on the

name of Aristotle's school, he reflects whimsically that his

views are "very peripatetic."

Russell proclaims that the business of art is to reveal

Platonic "essences," anything less being "the speculation of

schoolboys for schoolboys." This prompts Stephen's observation

that some students grow up to become masters: "— The

schoolmen were schoolboys first, Stephen said superpolitely.

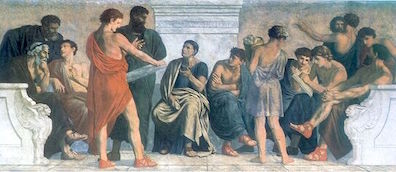

Aristotle was once Plato's schoolboy." Plato founded his

Academy in ca. 387 BC, and Aristotle studied there for fully

two decades, from age 17 to age 37. He left the Academy in 347

BC, one year after Plato's death, and in 335 he founded his

own school on the grounds of the Lyceum temple. He led this

so-called Peripatos until his death in 322. John

Eglinton mocks him as a mere child compared to Plato: "One can

see him, a model schoolboy with his diploma under his arm."

Stephen holds a different view: Aristotle absorbed the

teachings of his master, developed his own system of thought,

and trained a new generation of scholars in new disciplines,

new logical methods, a new philosophy.

Various associations branch off from this observation that

Aristotle studied with Plato but developed his own

philosophical system. One is the fact that Aristotelianism

survived and thrived long after its founder's death. "The

schoolmen" refers to the Scholastic philosophers of the

later Middle Ages, men associated with Europe's recently

founded universities: Paris, Bologna, Padua, Naples, Cologne,

Oxford, Cambridge, and others. They brought Aristotle's ideas

and his logical methods into their Christian culture by

translating his works into Latin, producing reams of

commentary on them, and incorporating his methods into their

own philosophical investigations. First and foremost, Stephen

is no doubt thinking of his beloved Thomas Aquinas.

He also is thinking of Aristotle's revision of the Platonic

doctrine of Forms. For Plato, the Ideas or Forms exist

independently of their manifestations in sensory experience

and are more real than those shadowy appearances. This-worldly

horses (to adapt the example that Stephen cites) are nature's

copies of an ideal Horse that exists on a truer plane of

being. Aristotle came to a different conclusion: the

constitutive forms exist only in conjunction with the matter

that they act upon, and they can be known only by abstracting

an intelligible principle from the class of empirical

phenomena in which it is manifested.

Stephen whimsically meditates on this process of logically

abstracting universals from particulars: "Unsheathe your

dagger definitions. Horseness is the whatness of allhorse."

The essence of horses is to be found not in Russell's "world

of ideas" but in the qualities that one observes hanging

around horses. "Whatness" translates the Scholastic term quidditas,

which Stephen has used in part 5 of A Portrait to

define beauty: "the scholastic quidditas, the whatness

of a thing." This medieval term translated Aristotle's Greek to

ti en einai, "the what it was to be" of a particular

thing. Although it represents Aristotle's empiricist effort to

bring Platonic universals down into the realm of sensory

experience, there is nothing empirical or experiential about

whatness, or, for that matter, forms. Everyone has seen

horses, but no one will ever see "horseness." Perhaps this

contradiction lies behind Stephen's bemused tone.

In a sentence just before these thoughts about form, Stephen

has glanced at Plato and Aristotle's disagreement about

the value of representational art: "Which of the two...would

have banished me from his commonwealth?" In the

sentences that follow, he contrasts the desire of Platonists

like Russell to transcend time, space, and mutability with his

own Aristotelian desire to ground abstract thinking in the

world of becoming: "Streams of tendency and eons they worship.

God: noise in the street: very peripatetic. Space: what you

damn well have to see. Through spaces smaller than red

globules of man's blood they creepycrawl after Blake's

buttocks into eternity of which this vegetable world is but a

shadow. Hold to the now, the here, through which all future

plunges to the past.

"God: noise in the street" recalls Stephen's

anti-transcendental effort (in Nestor) to imagine a radically

immanent divinity that inheres in the empirical world

rather than hovering beyond it. "Space: what you damn well

have to see" recalls his Aristotle-influenced thought

(in Proteus) that the visible world is

"ineluctable,"

not to be thought away by closing one's eyes. "Hold to the

now, the here, through which all future plunges to the past"

recalls his Aristotelian meditation (in Nestor) on the

mechanism by which the "infinite

possibilities" of a hypothetical future are reduced to

the hard, discrete historical facts that we call the past.

These three details share an interest in embodied

particularity––things taking shape in concrete lived

experience rather than in airy abstractions.

As for "peripatetic," a typically Joycean three-level

pun is involved. The Greek word means "walking around."

Aristotle's school acquired this name because the Lyceum

temple had many walkways, and ancient legends held that

Aristotle lectured while strolling about these spaces. But any

god who takes the form of "a shout in the street" also

deserves the name: he walks the streets instead of sitting on

an airy throne somewhere. Finally, the novel that Joyce wrote

is peripatetic because its characters spend an entire day

walking around those streets. If the right possibilities are

actualized, Stephen will not just imagine a peripatetic god.

He will bring a peripatetic book into the world.