In Wandering Rocks Tom Kernan thinks of the Rebellion

of 1798 led by United Irishmen like Lord Edward Fitzgerald: "They

rose in dark and evil days. Fine poem that is: Ingram. They

were gentlemen." Kernan quotes a line from The Memory of

the Dead, a poem written in 1843 by Irish mathematician,

economist, and poet John Kells Ingram, whose Protestant

background, shared with many of the United Irishmen, appeals to him. Two years

later the patriotic poem was set to music and became a popular

republican anthem. Echoes of the poem and the song sound

through three successive chapters.

Gifford notes that

Kernan's "

They were gentlemen" (following his image of

Fitzgerald as a "Fine dashing young nobleman. Good stock, of

course") is "A typical 'west Briton' phrase used to exonerate

Anglo-Irish Protestant revolutionaries (such as Fitzgerald,

Wolfe Tone, Emmet—and even Parnell) from the sort of blame due

the

croppies." The United

Irishmen movement of the late 18th century was truly ecumenical,

supported by patriots both Catholic and Protestant, though the

latter were mostly Presbyterians and Methodists, not members of

the Ascendancy class's official Church of Ireland.

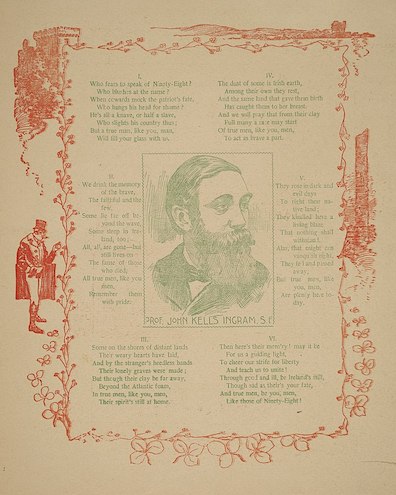

Ingram was born in 1823 to an Ulster Scots family living in the

southeastern corner of County Donegal, near Lower Lough Erne.

Although he considered Ireland unready for independence he

abhorred tyranny and

The Memory of the Dead celebrates

the sacrifices of the men killed in '98. He wrote the poem in

March 1843 while a student at Trinity College, Dublin and

published it anonymously on 1 April 1843 in

The Nation,

a newspaper dedicated to repealing the

Act of Union. In 1845 John

Edward Pigot set it to music for voice and piano. Despite

Ingram's distrust of militant nationalism the ballad entered the

pantheon of republican songs, and its tune has often been piped

at the funerals of fighters.

Douglas

Hyde translated the text into Irish.

Ulysses quotes

the English lines highlighted here in boldface:

Who fears to speak of Ninety-Eight?

Who blushes at the name?

When cowards mock the patriots' fate,

Who hangs his head for shame?

He’s all a knave or half a slave

Who slights his country thus;

But a true man, like you, man,

Will fill your glass with us.

We drink the memory of the brave,

The faithful and the few:

Some lie far off beyond the wave

Some sleep in Ireland, too;

All, all are gone—but still lives on

The fame of those who died:

All true men, like you, men,

Remember them with pride.

Some on the shores of distant lands

Their weary hearts have laid,

And by the stranger's heedless hands

Their lonely graves were made;

But, though their clay be far away

Beyond the Atlantic foam,

In true men, like you, men,

Their spirit's still at home.

The dust of some is Irish earth;

Among their own they rest;

And the same land that gave them birth

Has caught them to her breast;

And we will pray that from their clay

Full many a race may start

Of true men, like you, men,

To act as brave a part.

They rose in dark and evil days

To right their native land:

They kindled here a living blaze

That nothing shall withstand.

Alas, that Might can vanquish Right!

They fell, and pass'd away;

But true men, like you, men,

Are plenty here today.

Then here's their memory—may it be

For us a guiding light,

To cheer our strife for liberty

And teach us to unite!

Through good and ill, be Ireland's still,

Though sad as theirs your fate;

And true men be you, men,

Like those of Ninety-Eight.

Tom Kernan confuses the musical version of Ingram's poem

with The Croppy Boy:

"Ben Dollard does sing that ballad touchingly. Masterly

rendition. / At the siege of Ross did my father fall."

Although the croppy boy is Catholic and the rebels of Ingram's

Memory were Protestant, Kernan's slip is understandable

because both ballads tell stories of patriots who lost their

lives in the Rebellion of '98. And, as Ruth Wüst points out in

a personal communication, both were published in the same

paper. The Croppy Boy appeared in The Nation

in 1845, two years after the publication of Ingram's poem and

the same year in which the poem was set to music.

The two compositions remain linked in Sirens. As

Bloom listens to Ben Dollard singing The Croppy Boy he

doubly misremembers a line of The Memory of the Dead:

"Who fears to speak of nineteen four?" (It seems

possible that Joyce here is using his protagonist's proclivity

for getting details wrong to make a joking reference to the

date of his own novel's action, 1904.) At the end of the

chapter, the men who have been listening to Dollard's

performance drink a toast to one another inspired by the

refrain at the end of the song's first stanza:

— True men like you men.

— Ay, ay, Ben.

— Will lift your glass with us.

They lifted.

Tschink. Tschunk.

Echoes are still lingering in Cyclops: "So of course

the citizen was only waiting for the wink of the word and he

starts gassing out of him about the invincibles and the old

guard and the men of sixtyseven and who fears to speak of

ninetyeight and Joe with him about all the fellows that

were hanged, drawn and transported for the cause by drumhead

courtmartial and a new Ireland and new this, that and the

other." The Citizen uses the poem's title both as a toast and

as an aggressive challenge to the uncomprehending Bloom: "—The

memory of the dead, says the citizen taking up his

pintglass and glaring at Bloom."