Nowhere in her book does Reynolds note the most compelling

reason to suppose that Joyce is alluding to the lines from Purgatorio,

which is contextual: both passages involve the younger man's

response to a violent environmental disturbance. Stephen's

loud and licentious verbal pyrotechnics are followed by a huge

thunderclap, which makes him turn instantly pale, "and his

pitch that was before so haught uplift was now of a sudden

quite plucked down and his heart shook within the cage of his

breast as he tasted the rumour of that storm." Long after

leaving the Catholic church Joyce continued to hear in thunder

the voice of an angry God, and he gives Stephen the same fear

that "the god self was angered for his hellprate and paganry."

He tries to laugh it off, joking that "old Nobodaddy was in

his cups," but others can see that "this was only to dye his

desperation as cowed he crouched in Horne's hall." Bloom

attempts to allay his terror by telling Stephen that "it was

no other thing but a hubbub noise that he heard, the discharge

of fluid from the thunderhead, look you, having taken place,

and all of the order of a natural phenomenon."

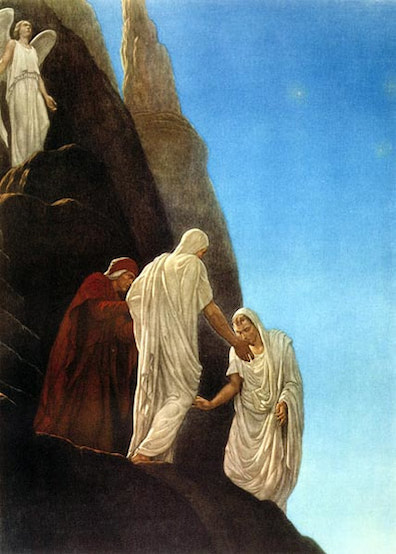

Similarly, in Purgatorio 20 an earthquake terrifies

Dante: "I felt the mountain tremble / as though it might

collapse, and a chill, / like the chill of death, subdued

me.... Then there rose up a great cry all around us" (127-33).

Neither he nor Virgil knows what to make of it, but cantos 8

and 9 have shown that fear is an inappropriate response on

this mountain that restores human innocence. After Virgil

tells Dante not to be afraid the two men hear "Gloria in

excelsis Deo" in the souls' cries and stand "stock still

and in suspense, / like the shepherds who first heard that

song" (136-40). In Dante's exacting symbolic craft this

allusion suggests that Christ is somehow coming to earth to

liberate mankind from sin. The prediction is fulfilled a few

lines later when a shade joins Dante and Virgil on their path

around the mountain, much as "Christ, / just risen from the

cave that was His sepulcher, / revealed himself to two He

walked with on the road" to Emmaus (21.7-9). It is Statius,

just released from his long purgatorial confinement, and he

tells them that the mountain "trembles when a soul feels it is

pure, / ready to rise, to set out on its ascent, / and next

there follows that great cry" (58-60). Virgil was right, then,

to say that there was nothing to fear, though he could not

have said why.

Readers who find the allusion to Dante credible may

nevertheless wonder why Joyce bothered to put it in his text.

Virgil is a non-Christian guide who shows Dante the Christian

realities of Hell and Purgatory. Bloom is a non-Christian

guide who urges Stephen not to view the storm through a

religious lens. Does Joyce mean for the contrast to show one

freethinker leading another astray? This seems unlikely,

though the narrative of Oxen does urge such a view,

adopting the voice of John Bunyan: "But was young Boasthard's

fear vanquished by Calmer's words? No, for he had in his bosom

a spike named Bitterness which could not by words be done

away.... But could he not have endeavoured to have found again

as in his youth the bottle Holiness that then he lived withal?

Indeed not for Grace was not there to find that bottle. Heard

he then in that clap the voice of the god Bringforth or, what

Calmer said, a hubbub of Phenomenon?" This narrative voice,

and other theocratic ones in Oxen, can hardly

represent Joyce's own views, for he too was, in Stephen's

words, "a horrible example of free thought."

Oppositely, one could argue that Joyce meant for the contrast

between the two guides to show the superiority of secular

thinking: non-Christian Bloom interprets thunder through sound

scientific principles rather than the fanciful and savagely

judgmental medieval theology that non-Christian Virgil has to

defend. Such an approach would better suit the irreverent

logic of Ulysses, but it seems tendentious. The end of

Eumaeus and the beginning of Ithaca feature

Stephen and Bloom as independent intellectual agents exploring

areas of agreement and disagreement, discussing "sirens,

enemies of man's reason," valuing free thought: "Both

indurated by early domestic training and an inherited tenacity

of heterodox resistance professed their disbelief in many

orthodox religious, national, social and ethical doctrines."

But if Dante's story enters the text of Oxen only as

an example of how not to interpret thunder, then the allusion

is not very tightly focused. Joyce usually brings passages

into intertextual dialogue by means of highly specific

analogues, but Virgil has nothing to say about the shaking of

the mountain.

These opposed readings both assume that the central point of

the comparison is to somehow decide the conflict between

religious and secular reasoning. That conflict is certainly

the focus of the narrative in Oxen, but it need not be

the primary reason for echoing Purgatorio 20. Bloom's

effort to correct Stephen's mistaken understanding is a very

Virgilian undertaking, but so is his generous sympathy, and

here the two passages are more exactly analogous. Bloom tries

to comfort Stephen's fear without understanding the life

experience that has produced it: a man of little faith, he has

never been terrorized by Irish Catholic threats of eternal

damnation. Similarly, Virgil tries to comfort Dante's fear

without understanding what has caused the earthquake or the

great revivalist shout. In Hell Virgil can confidently say

things like "Have no fear while I'm your guide" because he

knows the place well and is divinely commissioned to command

its inhabitants—though even there his confidence is sometimes

misplaced. In Purgatory he can only offer vague reassurances

about things that he understands poorly. But his parental

impulse to protect, console, and guide Dante remains as

important as ever.

Bloom feels exactly these impulses toward Stephen, and his

effort to console him in a moment of existential crisis

distinguishes him from all the drunken young men at the table.

While they can only applaud Stephen's clever blasphemies or

mockingly reprove them, Bloom responds to his fear

sympathetically and attempts to allay it. A rational

secularist moving through a world shaped by Christian belief,

he takes religion seriously enough to appreciate its

consolations and costs for human beings, just as the

rationalist Virgil does.

Oxen of the Sun only hints at resemblances between

Bloom and Virgil, just as it only hints at the possibility of

friendship between Bloom and Stephen (another such hint comes

several pages earlier when Bloom's witty disparagement of the

Catholic church makes Stephen "a marvellous glad man"). The

two men merely share a stage in this chapter and the next,

interacting very little, but in Eumaeus and Ithaca

they meet, spend time together, and converse. In those

chapters the analogy with Virgil and Dante is strengthened by

a succession of increasingly explicit allusions to things that

happen in Inferno and Purgatorio: the leftward

turns though Hell, its collapsed bridge, the growing mental integration of the two

protagonists, the interview with Ulysses, the vision of the stars after

emerging from Hell, the image of

Virgil as a lantern-bearer and the echo of Psalm 113,

and finally the terrible pathos of parting in the garden.

These later allusions establish beyond any doubt that Joyce

intended for his protagonists to reenact aspects of Dante's

story.