Stuart Gilbert

(1930) heard in this section "an anticipation of an early Church

style which is in advance of its context in the episode" (279).

It would be interesting to know his basis for making that claim.

Weldon Thornton (1968), in sharp contrast, heard an allusion to

the prologue of

Everyman, which would mean that Joyce

was jumping

ahead of the historical context, going

directly from the late 10th century to the late 15th. Robert

Janusko (1983) was persuaded by Thornton's identification. Don

Gifford (1988) agrees that the first paragraph echoes the play's

prologue, but he characterizes the entire section, quite

unspecifically, as "Middle English prose." Declan Kiberd (1992)

appears to believe that the influence of the play continues

through both paragraphs, and Jeri Johnson (1993) makes that

claim explicitly. Sam Slote (2012), who like Thornton does not

attempt to characterize the styles of the chapter, does agree

that the first sentence alludes to

Everyman.

Like other morality plays,

Everyman uses personified

abstractions to represent its protagonist's struggle for

spiritual wellbeing. Summoned to appear before God and make an

account of his life (the play's full title is

The Somonyng

of Everyman), Everyman tries to convince Fellowship,

Kindred, Cousin, and Goods to accompany him, but they all

refuse. Good Deeds feels too weak to join him, but she

introduces him to her sister Knowledge and he goes with her to

see Confession, after which Good Deeds feels strong enough to

make the journey. At the end of the play, Everyman climbs into

his grave with Good Deeds, dies, and ascends to heaven, the

lesson being that your good deeds, justified by God's grace, are

all that you can take with you.

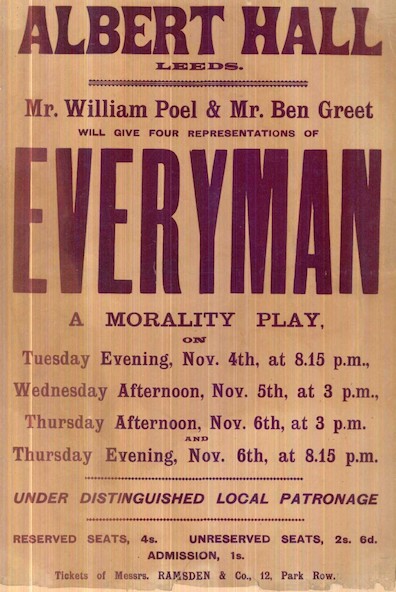

The play apparently was performed often in the decades following

its composition, and a modern stage adaptation with a female

lead was performed in the U.K. and the U.S. from 1901 to 1918.

Two films based on the adaptation were released in 1913 and

1914. Joyce might well have heard of one or another of these

recent enactments. He would not have encountered any excerpts

from the script in Saintsbury's or Peacock's anthologies of

English prose, because it consists entirely of verse lines, but

he does seem to have perused the text of the play. The allusion

that Thornton detected occurs in the Messenger's prologue:

Man, in the beginning,

Look well, and take good heed to the ending,

Be you never so gay.

You think sin in the beginning full sweet,

Which in the end causeth the soul to weep,

When the body lieth in clay.

Here shall you see how fellowship and jollity,

Both strength, pleasure, and beauty,

Will fade from thee as a flower in May.

For ye shall hear how our Heaven-King

Calleth Everyman to a general reckoning.

Joyce's echo of these lines ("Therefore, everyman,

look to

that last end that is thy death") seems to be prompted by

the fact that Bloom and nurse Callan have been talking in the

previous paragraph about an unexpected death. Bloom's black

clothes have made the nurse fear some "sorrow," but she learns

that no one dear to him has died. His cheerful inquiry about

Doctor O'Hare, however, produces the news that this "young" man

has died of cancer. Callan, who is pious, prays for "God the

Allruthful to have his dear soul in his undeathliness," and the

two stand "sorrowing one with another." The hope that God will

save the dead man's soul triggers a new section of narrative

keyed to the lines from

Everyman.

The one-sentence opening paragraph then abandons the play's

idiom and echoes biblical language: "the dust that gripeth on

every

man that is born of woman for as he came naked forth from his

mother's womb so naked shall he wend him at the last for to go

as he came." Chapter 14 of the Book of Job begins, "

Man

that is born of a woman is of few days, and full of

trouble. / He cometh forth like a flower, and is cut down: he

fleeth also as a shadow, and continueth not" (1-2). Earlier, Job

has said, "

Naked came I out of my mother's womb, and naked

shall I return thither: the Lord gave, and the Lord hath

taken away" (1:21). Was Gilbert perhaps thinking of these

well-known verses being used in medieval homiletic writing when

he argued that the passage was written in an "early Church

style"? There is no way of knowing, but clearly the image of man

born of a woman exerts a much stronger influence on the

following paragraph than does anything in

Everyman.

Bloom is now "

the man" who has come into the hospital,

and Callan is "

the nursingwoman." He asks her not about

Mrs. Purefoy but about "

the woman that lay there in

childbed.

The nursingwoman answered him and said that

that

woman was in throes now full three days." She says that

"she had seen many

births of women but never was none so

hard as was

that woman's birth," and "

The man

hearkened to her words for he felt with wonder

women's woe

in the travail that they have of motherhood." Until some reader

discovers a medieval text that recurs to these two words with

comparable regularity, Joyce's second paragraph should probably

be regarded as a riff on verses from the Book of Job, perhaps in

the style of a real or imagined medieval sermon. Gifford's

"Middle English prose" is frustratingly generic, but his

instincts seem keener than those of Janusko, Kiberd, and

Johnson, for whom the fact that

Everyman is written in

verse never even registers as a problem.

This section echoes Middle English vocabulary much more

sparingly than the previous one echoed Old English. Only one

word needs glossing: "

unneth" recalls the Middle English

uneathe or

unethe = difficult, not easy. This

word derived from an Old English one,

uneaþe, and the

second paragraph contains several such echoes of the past.

Bloom's asking "how it fared with the woman" may possibly be

heard as a reprise of the previous section's echoes of "faring"

in

Ælfric's life of St. Cuthbert.

There are also several instances of alliteration in something

like the Anglo-Saxon manner. The most striking ones come near

the end: it is said that Bloom "

felt with wonder women's woe,"

and when he marvels that the attractive young nurse is still a

"handmaid" (i.e., not married) nine years after he first met her

in the hospital, the judgmental narrative harps on her sterile

menstruations: "Nine twelve bloodflows

chiding her childless."

(Joyce's letter to Frank Budgen mentions these periodic returns

to Anglo-Saxon alliteration.)

It is also worth noting that this section recapitulates the

false-start quality of the previous one. There, two sentences

powerfully reminiscent of Old

English verse relapsed into a Latinate style, before

settling into five paragraphs of Anglo-Saxon prose in which an

alliterative poem plays only a thematic role. Here, the action

begins with half a sentence reminiscent of a late medieval

verse play, before settling into a paragraph that sounds like

the (earlier?) Middle English prose that Joyce's historical model

might lead one to expect. Joyce evidently had some fun

painting outside the chronological and generic outlines of his

design. He also clearly enjoyed letting new narrative settings

express themselves in new styles. Bloom's arrival at the

hospital after wandering about all day calls for The

Wanderer, even if it is not in prose. His sad

talk with nurse Callan about a young doctor's death calls for

Everyman, even if its dating is too late. His entrance

into a common-room filled with wildly dunken talk and laughter

will likewise call for some fantastic

medieval travel stories.