The account of the journey begins in the rough Monto

district, on or near Tyrone Street where Stephen was knocked

down: "They both walked together along Beaver street or,

more properly, lane as far as the farrier's and the

distinctly fetid atmosphere of the livery stables at the

corner of Montgomery street where they made tracks to the

left from thence debouching into Amiens street round by the

corner of Dan Bergin's." There is no Beaver Lane, and as

Slote observes, Beaver Street is "not especially narrow," so

the prose evidently reflects someone's feeling threatened in

this wretchedly poor and crime-ridden part of town. That

someone is more likely Bloom than Stephen. A horse-shoeing

business ("farrier's") was located at 14-15 Beaver

Street, and the livery stable at 42 Montgomery (now Foley)

Street, where Beaver deadends, adds foul smells to the close

dark atmosphere. Here the identity of the person feeling

oppressed seems certain, because A Portrait of the Artist

has observed that Stephen welcomes the odor of "horse piss and

rotted straw." The two men, we learn, "made tracks"

toward Amiens Street––a cliché that often implies haste,

suggesting that Bloom cannot wait to get out of Monto.

Their turn onto the thoroughfare, which takes them past

Daniel Bergin's pub at 46 Amiens Street, is described as a "debouching,"

a rather recherché way of saying "emerging into the open." The

French word, which came into English in the 18th century,

means coming "from the mouth." It can apply to things like

rivers emptying into the sea, but it was often used to

describe a body of troops emerging from a town or other

enclosed space onto open ground. Joyce uses it in that way in

Lestrygonians when the narrative observes that "A

squad of constables debouched from College street,

marching in Indian file." In Eumaeus, applied to two

men emerging from narrower streets onto a broader one, the

word feels more than a little pretentious. It may well express

Bloom's sense of quiet triumph at having reached somewhat

safer streets.

Looking down Amiens Street for a cab, Bloom sees only one: "as

he confidently anticipated there was not a sign of a Jehu

plying for hire anywhere to be seen except a

fourwheeler, probably engaged by some fellows inside on the

spree, outside the North Star hotel and there was no

symptom of its budging a quarter of an inch when Mr Bloom, who

was anything but a professional whistler, endeavoured to hail

it by emitting a kind of a whistle, holding his arms arched

over his head, twice." The North Star Hotel at 26-30 Amiens

Street (now The Address Connolly) is a long city block from

the Montgomery Street corner, and elevated train tracks crowd

the space between, so Bloom's weak yoo-hoo signals appear

comically futile.

The narration too is inept. It says "confidently anticipated"

instead of "correctly feared." It informs readers that the cab

has probably been hired "by some fellows inside" before

observing the cab's location "outside the North Star hotel."

And who has ever heard of professional whistlers? Bloom's

awkwardness, and the awkward descriptions of his actions,

together threaten to obscure the very kind efforts that he is

making on his companion's behalf. A fourwheeler (a closed

carriage like the one taken to the cemetery in Hades)

would be more expensive than a two-wheel jaunting

car, but Bloom is determined to find Stephen a ride. His

search for "a Jehu plying for hire" contributes to the

sense of his urgent desire to help the young man. This slang

word for a fast driver comes from a biblical verse: "the

driving is like the driving of Jehu the son of Nimshi; for he

driveth furiously" (II Kings 9:20).

Failing to find a cab means more walking: "This was a

quandary but, bringing common sense to bear on it, evidently

there was nothing for it but put a good face on the matter and

foot it which they accordingly did. So, bevelling around by

Mullett's and the Signal House which they shortly reached,

they proceeded perforce in the direction of Amiens street

railway terminus." Wordiness, clichés, and obscure slang

(Gifford notes that "bevelling" means "moving or pushing")

here complicate a simple and straightforward action. "Mullett's"

was another grocery and public house at 45 Amiens Street,

right next door to Bergin's. The "Signal House," yet

one more such establishment at 36 Amiens Street, remains in

business today under the name J. & M. Cleary. This pub

tucked almost directly beneath the train tracks is one of the

oldest in Dublin. It has a rich history, and several films

have been shot on the premises. It merits a visit from all

Joycean tourists.

On the other side of Amiens Street sits the station where the

train tracks lead: "They passed the main entrance of the

Great Northern railway station, the starting point for

Belfast, where of course all traffic was suspended at

that late hour..." This railway was one of four major lines

with terminals in Dublin: trains for southeastern parts of

Ireland departed from the Westland Row station, trains

for the southwest from Kingsbridge, trains for the

west from Broadstone, and trains for

the north from Amiens Street, all four stations being served

by different railway companies. The Loopline under which

Bloom and Stephen have just walked connects the Westland Row

station and the one on Amiens Street (now Connolly Station) on

elevated tracks.

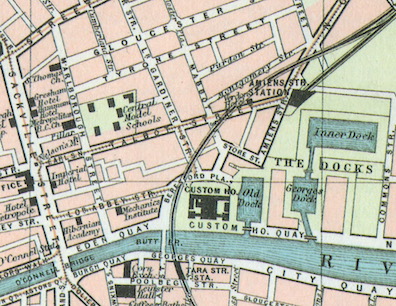

The sentence continues, "and passing the backdoor of the

morgue (a not very enticing locality, not to say

gruesome to a degree, more especially at night) ultimately gained

the Dock Tavern and in due course turned into Store street,

famous for its C division police station." Store is a

short but wide street with a right-angle turn in its middle

that in 1904 offered the only connection between Amiens Street

and Beresford Place. (Today, with the docks filled in, traffic

on Amiens can continue farther south.) The men pass an

entrance to the City Morgue at 2-4 Amiens Street, reach the

Dock Tavern on the corner, turn into Store Street, and then

pass a door to the Coroner's Court housed in the same building

as the morgue (this door goes unmentioned in the narrative,

but is illustrated in a photograph here).

The Dublin City Coroner's Court and City Morgue opened on

Store Street in 1902. Although the narrative describes it as "gruesome"

(based, apparently, only on knowing what the building

contains), its founding in fact represented a clean modern

solution to Dublin's longstanding problem of keeping people

who had died of unknown causes in conditions that were truly

gruesome: unrefrigerated, poorly lit, poorly ventilated, and

often filthy. In a 2021 blog

(lornapeel.com/2021/09/12/morgue), Lorna Peel describes the

new facility: "The purpose-built coroner’s court and morgue on

Store Street was designed by the city architect Charles J

McCarthy who had gone on a fact-finding tour of coroner’s

courts in England. It contained a court with a public gallery,

a jury box, retiring rooms and a waiting room for witnesses.

The mortuaries and post-mortem room were separate and to the

rear of the building. The viewing lobby was separated from the

mortuaries by glass screens so jurors and others called upon

to view the bodies on which inquests were being held could

observe them without actually entering the mortuaries." (Today

the morgue has moved to another part of town, but the

coroner's court remains on Store Street.)

A little farther down the same side of the street, they pass

the C Division police station. Calling it "famous" may

have something to do with police suppression of demonstrations

on Beresford Place. In 1899 opponents of the Boer War staged massive

demonstrations there and were met with massed police

forces. Slote notes that police lived in barracks in this

building only one block away from the large open Place, so

their pouring out of it to contain the crowds––a true "debouching"––could

possibly have made it notorious. The neutral term "famous"

seems characteristic of Bloom's guardedly ambivalent attitudes

toward republican insurrection. (Political demonstrations were

also held in Beresford Place in the wake of the Easter Rising

of 1916, as a photograph in another note on

this site shows.)

One more building on Store Street makes its presence known

when the narrative observes that Bloom "inhaled with internal

satisfaction the smell of James Rourke's city bakery,

situated quite close to where they were." The final

clause reflects the fact that the two men do not walk directly

past Rourke's: they jog left on Store just before the

triangular plaza on which the bakery fronts. But the pleasant

aroma coming from the nighttime baking calls forth a torrent

of playful verbal associations in Bloom's consciousness. His

olfactory delight makes a kind of bookend to the "fetid"

stench of horses that assaulted his nose on Montgomery Street,

announcing a happy end to a journey that seemed foreboding at

the outset. This pairing of two striking odors may be taken as

evidence that Joyce conceived of the walk down Amiens Street

as one united action, starting shortly before the men reach

the thoroughfare and concluding shortly after they leave it.

§ If

design may govern in a thing so small, it may also involve the

grandest kind of planning in the novel, the analogy with

Homer's Odyssey. In Lotus Eaters Joyce's

cunning artifice made Bloom's feet sketch two huge

question marks on the Dublin pavements, evoking his

aimless lotus-like confusion. The opening paragraphs of Eumaeus

may be doing something similar by having Bloom and Stephen

walk southeast to Amiens Street, south down the length of the

boulevard, and southwest to Beresford Place. Gifford observes

that the route is "circuitous, circumspect––as are both

Odysseus's and Telemachus's approaches to Eumaeus's hut in The

Odyssey." The mortal peril that Homer's heroes skirt as

they return to Ithaca seems to be reflected in Joyce's heroes'

late-night trek through darkened streets in a dangerous part

of town, skirting prostitutes, thieves, drunks, dead bodies,

and policemen. The cabman's shelter, like Eumaeus's house,

provides a place of relative safety where they can carefully

assess one another and plot their next moves.