When a sand-spreader passes Bloom and Stephen in the

chapter's second paragraph, "the elder man recounted to his

companion à propos of the incident his own

truly miraculous escape of some little while back." The

hyperbole feels of a piece with the exotic expression. À

propos, literally "to the purpose," is a useful phrase

and sounds more elegant than "in relation to," but since it

entered English centuries ago and is commonly spelled

"apropos," in this form it looks pretentious. (Slote,

Mamigonian, and Turner observe that it gained currency in

English in the 17th century. I will follow their lead in

noting the eras in which the chapter's French terms were

anglicized, as documented by examples in the OED.) The

phrase recurs four more times in Eumaeus, now spelled

in the usual English way but still italicized––as if the

person writing the chapter knows about its normalization but

still wants to be admired for using French.

The third paragraph calls the sex workers of the Monto "fast

women of the demimonde." This word has a

relevance to prostitution that English words like "underworld"

or "underclass" do not, and, as it was fairly new in 1904,

using it shows some cultural awareness. Alexandre Dumas coined

the word in his play Le demi-monde (1855) to refer to

courtesans on the fringes of respectable society––a

"half-world" of marginal women kept in fine clothes, and

helped out of them, by wealthy patrons. Writers in Victorian

England quickly adopted the term so there is probably no need

for italics, but readers may wish to give the narrator style

points for being up to date on recent French expressions.

Problematically, though, this term for rich Parisian

mistresses is applied to Dublin's desperate whores. The ironic

mismatch could possibly be meant to mock the grimy reality of

Monto, but it seems more likely that in reaching for a classy

name the narrator is betraying his own imperfect

sophistication.

Other French borrowings in the same paragraph support this

view, as they seem designed merely to sound cultured. Being "En

route" to Eccles Street, a phrase adopted in the

18th century, does not communicate information any better than

being "on the way"––it merely boasts a chic elegance.

Similarly, at the end of this paragraph Bloom comments on "the

desertion of Stephen by all his pubhunting confrères

but one." Anglicized since the 15th century, this word has

nothing but a snooty air to recommend it over the English

"companions."

Several short paragraphs later, Bloom stands "on the qui

vive"–– "on the alert"––as Stephen walks over to

meet Corley under the railway bridge. Like demimonde

this phrase (it entered English early in the 18th century) is

worth admiring for its appropriateness to the narrative

context. It originated with sentries' challenges: the correct

answer to Qui vive? ("[Long] live who?") would have

been "Vive le roi!" ("[Long] live the king!"). The

vigilance of sentries has relevance to the present situation,

as some unknown person has just hailed Stephen from the

shadows, late at night, in a bad part of town. But just as

calling Bella Cohen's whores demimondaine is a bit over the

top, Bloom's standing sentry duty as Stephen talks to Corley

seems more than a little melodramatic. Bloom has already

evinced discomfort walking in this

area at night, and now the French phrase imparts an air of

comical seriousness to his vigilance.

Melodrama tips over into absurdity in the cabman's shelter

when Bloom orders some coffee and bread "with characteristic sangfroid,"

a term taken from French in the middle of the 18th century.

Literally "cold blood," it denotes composure, calmness,

imperturbability––surely an odd condition to attach to the

ordering of coffee. In another act of overstatement Stephen is

now called Bloom's "protégé"––a

"protected one" being shown the ropes by an older, more

experienced guide, according to a phrase adopted in the late

18th century. The two men are further said to engage in a "tête-à-tête"

or "head-to-head" conversation. This phrase, acquired in the

late 17th century, denotes private conversations from which

others are excluded, and again there is some appropriateness:

Stephen and Bloom are sitting at a table by themselves, not

yet talking to others in the shelter. However, the phrase's

connotations of intense intimacy could hardly be less "apropos"

(that word makes another appearance here), given Stephen's air

of barely tolerating Bloom. Like qui vive, these three

new terms seem designed to exalt Bloom, flattering him for

taking charge of a dicey situation, but their excessiveness

invites laughter.

After the sailor interrupts the tête-à-tête the narrative

observes, "apropos" of Bloom's ideas of traveling to

England, that a steamship line from southeastern Ireland to

Wales is "once more on the tapis" in the

relevant government agencies. This expression too was

anglicized in the late 17th century. Literally "on the carpet"

and metaphorically "under discussion," it is less well known

than others in the chapter (most English dictionaries do not

include it), creating an impression of out-of-the-way

learning. But even if the italics may be justified for that

reason, the use of an exotic word where a common one would do

hinders the communication of information more than it advances

it.

A less rare but still pretentiously recherché term appears in

the next paragraph when Bloom imagines touring remote spots in

Ireland. He reflects that, if reports are true, there are

places in Donegal where "the coup d'œil was

exceedingly grand." Literally a "stroke of the eye," this

expression, absorbed into English in the 18th century, refers

to a glance that quickly takes in a scene––what strikes the

eye, in other words. The OED cites examples from

earlier English travel writing in which the phrase is paired

with adjectives like "beautiful" and "magnificent." Its use

here feels more to the point than sangfroid, protégé, and

tête-à-tête, but tonally ill-advised. Using an uncommon

continental expression to describe a scene in rural Ireland is

surely un peu pretentious.

In the same discussion of Bloom's wanderlust, the narrative

calls on a more familiar French term. Common working men like

himself, he opines, "merited a radical change of venue

after the grind of city life." Literally a "coming," this word

carried the metaphorical sense of an assault in the 14th

century, but since the 18th it has come to mean a place where

something (a law trial, a performance, a competition) is

scheduled to occur. Most readers will recognize the word, but

they may wonder why it is being applied to a tourist trip. A

similarly strange usage occurs when the sailor's story of a

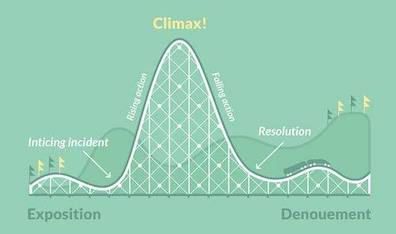

knifing is described as a "harrowing dénouement."

Literally an "untying," this French word adopted in the middle

of the 18th century usually refers to the point late in a play

or novel where plot complications are resolved or clarified.

The sailor's story has involved nothing more complicated than

a threat of violence being followed by actual violence. Later

in Eumaeus this usage is repeated when the business of

drunken young men getting into trouble is described as "the

usual dénouement." Both uses of the word feel

forced and pointless.

Several sentences later, Stephen and Bloom respond to an

inane comment by exchanging "glances, in a religious silence

of the strictly entre nous variety." This

expression meaning "between us," current in English since

the 17th century, usually precedes some statement that

the speaker hopes will be held in confidence. Since "just

between you and me" communicates exactly the same intention,

an English speaker's use of the phrase will probably always

sound slightly precious. The same could be said, several

paragraphs later, of calling Murphy "Our soi-disant

sailor." One may wonder why this expression, adopted in the

mid-18th century, is ever necessary. If "self-styled" or

"self-proclaimed" convey the same idea in English that

"self-saying" does in French, why not use the ready-to-hand

expressions? This phrase too is repeated later in the chapter:

"the soi-disant townclerk Henry Campbell."

Continuing its misleading suggestion of an entre-nous

tête-à-tête, the narrative now characterizes Stephen as a person

with whom Bloom shares secrets: "— Our mutual friend's

stories are like himself, Mr Bloom,

apropos of knives,

remarked to his

confidante sotto voce."

Confidant and confidante came into English in the 18th century.

(The

OED suggests that the feminine form may have been

"formed to represent the sound of the French confidente, and

that the masculine confidant was formed from it. The feminine is

the more common in use.") Both words denote someone in whom one

confides. Bloom does repeatedly divulge confidences to Stephen

in

Eumaeus, but Stephen seems anything but receptive,

and does not reciprocate, so the label does not suit him.

Up to this point, one may fairly conclude that the ironic

disconnects between words and events suggest bumbling ineptitude

on both the narrator's part and Bloom's. But at some point very

near the middle of the chapter this contrary tide begins to

turn. Relating an ethnic slur about Italians, Bloom supposes

that they poach neighbors' cats at night "so as to have a good

old succulent tuckin with garlic

de rigueur off

him or her next day." The stereotyping of Italians is

buffoonish, but the use of French is more finely calculated.

Adopted in the mid-19th century,

de rigueur, literally

"of strictness," refers to something made obligatory by current

social customs. Applying a phrase born of the French love of

haute fashions to the low-class southern Italian love of garlic

(with cat flesh, no less) is so strikingly weird that it is hard

to imagine it being anything other than an arch attempt at

humor. If so, then either Bloom or the narrator is starting to

deploy irony less self-destructively.

Irony seems even more clearly intended when, in recounting a

discussion of shipping and shipwrecks, the narrative remarks

that the keeper of the shelter is "evidently

au fait."

Literally "to the fact," this phrase acquired in the mid-18th

century means that one is knowledgeable about something,

up-to-date on the facts. In this case the keeper, far from

saying anything insightful, has only implied that he has some

special, undeclared knowledge of shady doings in the shipping

business: "There were wrecks and wrecks, the keeper said." Crude

conspiracy-theory intimations hardly make one au fait. The same

ironic edge attends another French word employed shortly later.

When the sailor returns to the alcohol-free shelter, having

taken advantage of his absence to imbibe some liquor, he sings a

rough sea chanty, "introducing an atmosphere of drink into the

soirée."

The French tradition of holding elegant "evening" parties, which

English speakers have acknowledged since the late 18th century,

is so dissimilar from the shabby gathering in the cabman's

shelter that one can only assume a sarcastic intent.

The second half of the chapter also features many French terms

whose use, while not ironically cutting, is at least

straightforward. Bloom imagines a hotblooded Mediterranean

husband killing "his adored one as a result of an alternative

postnuptial

liaison by plunging his knife into

her." This familiar French word adopted by English speakers in

the early 19th century, literally a "binding," can refer to any

connection formed between individuals or groups, but more

specifically it denotes an adulterous relationship. The chapter

later employs this meaning a second time when Bloom,

contemplating his own marriage, thinks of "many

liaisons

between still attractive married women getting on for fair and

forty and younger men." Another very familiar French word

appears when the keeper makes a joke and is rewarded with "a

fair amount of laughter among his

entourage."

This useful term for a group of friends, followers, or

associates, appropriated in the middle of the 19th century, is

literally a "surrounding."

When Bloom shows Stephen an old photo of Molly "in evening dress

cut ostentatiously low for the occasion to give a liberal

display of bosom," the narrative recalls his reading of a

pornographic novel earlier in the day, noting that he "looked

away thoughtfully with the intention of not further increasing

the other's possible embarrassment while gauging her symmetry of

heaving

embonpoint." Literally "in good

condition" (from

en bon point), this compound word

denotes healthy plumpness, sometimes specifically with reference

to a woman's breasts. It can imply excessive fat, but in

The

Sweets of Sin the connotations are clearly positive, and,

although

Ulysses makes clear that

Molly has put

on a few pounds over the years, most Dubliners do not seem

to regard that as a bad thing. Lenehan

relishes her

mammary amplitude in

Wandering Rocks, and in

Lestrygonians Nosey Flynn says

, "She’s well

nourished, I tell you. Plovers on toast." Here in

Eumaeus

the French word seems to be not so much flattering Bloom as

inhabiting his obsessive fantasies. Even the word "heaving"

comes straight from

Sweets of Sin, and "gauging her

symmetry" comes from the mnemonic he pondered in

Aeolus.

Two words follow that are unremarkable except for their

superfluous italics. Bloom thinks that Stephen is "educated,

distingué."

The French version of "distinguished" gained currency in English

in the early 19th century but conveys no difference of meaning.

Few English speakers will fail to understand the meaning of "

fracas,"

as applied to an 1890 brawl between Parnellites and

anti-Parnellites that supposedly involved the former

breaking up the printing presses of

United Ireland. The

French word, absorbed into English in the 18th century, comes

from the Italian

fracasso (noise, crashing, uproar,

din), which in turn may possibly derive from the Latin

frangere

(to break).

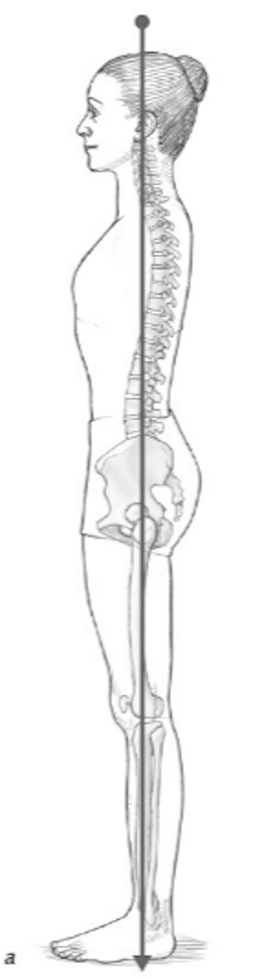

A third word in this part of the chapter suggests some mastery

of both English and French meanings. Bloom recalls that Parnell

thanked him for restoring his hat "with perfect

aplomb"

(19th century). Most English speakers will know the usual

meaning of assured self-confidence, but not the etymological

sense of being "upright." Perpendicularity is determined in

France

à plomb, by the lead weight of a plumb

line. In this case, the narrator seems to be representing

several known qualities of Parnell: his commanding presence, his

moral stature (he is always treated respectfully in

Ulysses),

and his tall, ramrod-straight physical bearing.

The sense of knowledgeable control is maintained in the last few

pages of the chapter, starting with Bloom's proposal that he and

Stephen "close the

séance" and leave the shelter.

This noun, adopted late in the 18th century, is known to most

English speakers today only in connection with people gathering

to receive messages from the dead, but it has a wider range of

meanings in French. Literally a "sitting," and by extension a

"session," it can refer to assemblies and meetings, and also to

other seated activities like posing for a portrait or watching a

film. Its use here is contextually appropriate––the two men have

sat for some time conducting a conversation––but the narrator

also seems to be commenting ironically on the gathering in the

shelter, which little resembles a legislature, court, or

council. That arch tone is certainly intended in the following

sentence, when Bloom and Stephen leave "the shelter or shanty

together and the

élite society of oilskin and

company." This word, imported into English early in the 19th

century, denotes a small group whose abilities make them

superior to the rest of society––hardly the case here.

Discussing music with Stephen in the street outside the shelter,

Bloom remarks that "he had a

penchant, though

with only a surface knowledge, for the severe classical school

such as Mendelssohn." Calling Mendelssohn severely classical

betrays limited musical knowledge––his compositions combine the

Mozartian formal control of the old classical style with the

expressive emotional fervor of the romantic movement––but the

use of the French word is unremarkable. Literally an

"inclining," English speakers have used it since the 17th

century to express a strong inclination or liking, and its

pronounciation is regularly anglicized as PEN-chunt.

In the next sentence Bloom refers to the "old favorites" of the

Dublin concert repertoire and mentions "

par excellence

Lionel's air in

Martha,

M'appari." Literally "by

excellence," the phrase means "above all" or "pre-eminently" in

French and has carried the same meaning in English since the

16th century. Another perfectly unremarkable usage comes when

Bloom imagines that Stephen's lovely tenor voice might gain him

"an

entrée into fashionable houses in the best

residential quarters." The French word means simply "entry," but

since the 18th century it has given English a way of denoting

permission to enter places normally barred to outsiders.

In the sense intended in the penultimate paragraph of

Eumaeus,

a "

contretemps," anglicized in the early 19th

century, is something happening "against time"–– an inopportune

occurrence or mishap. In this case the street sweeper's horse is

depositing three large smoking turds on the stones which Stephen

and Bloom are approaching. That fact might be regarded as

untimely, but Bloom, "profiting" from the driver's humane

decision to let his animal rest while relieving himself, takes

the opportunity to safely pass by the stopped machine (a less

"miraculous escape" than before, perhaps). Some command of the

implications of

contre is implicit in the double action

narrated here––a threat to forward progress followed by a

countering of that threat.

By the time Stephen and Bloom are again seen engaged in a "

tête-à-tête"

in the chapter's final sentence

, their interaction has

warmed to the point that this term for an exclusive one-on-one

conversation seems quite possibly merited. Engaged in animated

discussion of topics of mutual interest, they occupy an

intensely private space that the driver of the car is "utterly

out of." Readers may realize, in retrospect, that the

improvement in the relationship of the two protagonists has been

occurring in tandem with the narrator's subtly improving uses of

French. For some time, the fancy French expressions have ceased

to backfire on the narrator or subject Bloom to ridicule. It

seems that French may, in fact, be an appropriate native

language for Dubliners who aspire to a measure of continental

sophistication.

Many of the French expressions detailed here suggest that the

narrative is performing

free indirect approximation

of Bloom's states of mind, and indeed his quoted speech shows a

penchant for French expressions like the ones employed by the

narrator: "— A gifted man, Mr Bloom said of Mr Dedalus

senior, in more respects than one and a born

raconteur

if ever there was one.

" No one should suppose that Bloom

is narrating the chapter, but its prose does display

affectations that he might adopt were he somewhat better

educated and more seriously devoted to writing.

Eumaeus

makes Bloom a risible figure at the beginning only to redeem him

by the end, and it does something similar with French

expressions, modulating their use so that by the final pages

they feel less pretentious, more natural.

Joyce may have done this to further the impression that the

feckless Bloom could possibly be a worthy companion for

Stephen. The younger man is fluent in French and fills the

pages of Proteus with a blizzard of foreign

expressions: French, Italian, Latin, Greek, German, Spanish,

Swedish, Irish. He wields such idioms far more ably than the

narrator of Eumaeus but, even when the prose of the

later chapter appears inept, its flurry of French, Italian,

and Latin words recalls similar effects in Proteus. By

the end of the chapter Stephen is singing an "old German song"

to Bloom, in German. In Ithaca the two men exchange

the snippets of Irish and Hebrew that they know. The

multilingual borrowings that feel like ludicrous pomposity at

the beginning of Eumaeus offer something more by its

conclusion: a point of contact between two men who, according

to the first page of Ithaca, "Both preferred a

continental to an insular manner of life."