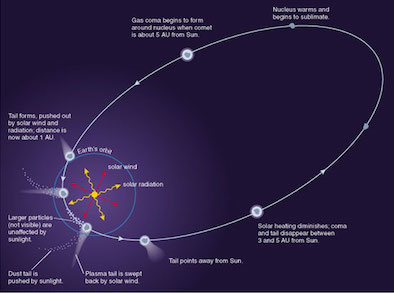

Comets have "almost infinite compressibility" in the

sense that their spectacular tails are composed of tiny

particles of dust and water vapor that the sun's intense

radiation has boiled off a traveling ball of ice and rock.

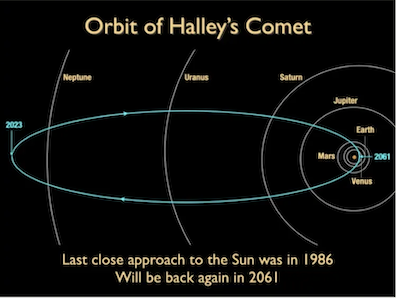

Also long are their "vast elliptical egressive and

reentrant orbits," which in reentry take them to

a point near the sun ("perihelion") and in egress to a

point far away from it ("aphelion"). Only in close

proximity to the sun do comets put on the wonderfully "hirsute"

shows that awe human beings––Finnegans Wake calls them

"creamtocustard cometshair" (475.15) and imagines "combing

the comet's tail up right and shooting popguns at the

stars" (65.10-11). When they return to the deep, dark, cold

haunts of the outer planets, these iceballs "chancedrifting

through our system" (FW 100.33-34) fade away

into obscurity.

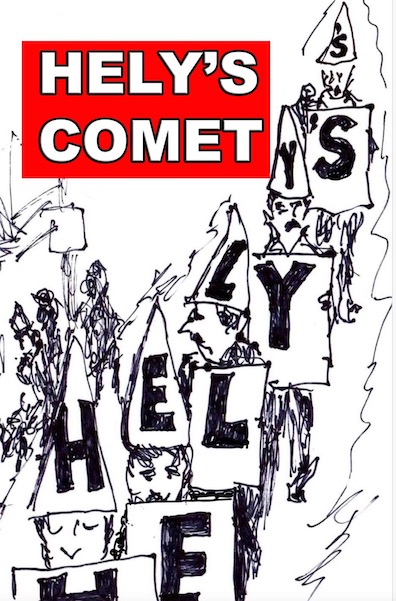

Comets are first introduced, inconspicuously, in Lestrygonians.

As Bloom stands on the O'Connell bridge worrying that Boylan

could give Molly a sexually communicable disease, he notes

that the "Timeball on the ballastoffice

is down. Dunsink time." This large ball on a pole in

downtown Dublin dropped once every 24 hours, letting people on

the quays know the exact time as communicated by wire from the

Dunsink observatory. The details are serendipitously similar

to those of a cosmic iceball that drops down into view at

certain predictable times. Almost immediately after this,

Bloom sees "A procession of whitesmocked men" moving

slowly toward him––another vision of the comet, with its

streaming white tail. As ever, Joyce's ingenuity here is

astonishing: Hely's men predict the

arrival of Halley's comet in 1910, as regular as a "Timeball"

after its usual 75-76 year absence. Finnegans Wake

documents Joyce's awareness of the fact: "like sixes and

seventies as eversure as Halley's comet" (54.8).

The 9th section of Wandering Rocks shows that the

linkage implied in Lestrygonians––Boylan visiting

Molly, a comet visiting the earth––is not accidental. Lenehan

and M'Coy see Bloom perusing books at a stall, prompting

Lenehan to recall that "I was with him one day and he bought a

book from an old one in Liffey street for two bob. There were

fine plates in it worth double the money, the stars and the

moon and comets with long tails. Astronomy it was

about." Then, laughing, "I'll tell you a damn good one

about comets' tails, he said. Come over in

the sun." The story concerns a night when the Blooms

shared a jaunting car with two

others coming back from Glencree over the dark deserted summit

of Featherbed Mountain, at "blue o'clock the morning" on "a

gorgeous winter's night." On one side of the car Bloom was

"pointing out all the stars and the comets in the heavens to

Chris Callinan and the jarvey: the great bear and Hercules and

the dragon, and the whole jingbang lot." On the other side

Lenehan was lecherously "lost, so to speak, in the milky way"

of Molly's breasts as the car's bumpy motion repeatedly threw

them together.

The linkage between comets and sexual hankypanky in this

scene involves yet another suggestive image. Molly that night

was wearing a "boa" which Lenehan kept strategically

adjusting around the curves of her body: "I was tucking the

rug under her and settling her boa all the time. Know what I

mean?" A boa is a long, light, feathery thing, quite

comparable to a comet's tail, and it is wrapped around a warm

body, like a comet snaking its way around the sun––as Joyce

emphasizes by having Lenehan tell M'Coy to come over in the

sun to hear about comets' tails. Readers may recall that

Molly's attractive warmth is a regular feature of Bloom's

erotic reveries.

Another such evocative image has appeared in the 5th section

of Wandering Rocks when Boylan "drew a gold watch

from his fob and held it at its chain's length." As in

the Lestrygonians passage, the suggestions of this

image are shaped by what comes immediately before and after.

In the preceding sentence, the sandwichboardmen are again seen

plodding along Grafton Street, this time through the windows

of Thornton's shop. Three short sentences later, there is a

reminder of Lenehan and the comets when Bloom is seen (via interpolation)

looking at books on the cart in Merchant's Arch. The watch and

chain––round head, long tail––clearly are intended to evoke

comets, the phallus, Blazes Boylan, and an unhappy husband.

But shape is not the only imagistic feature working quietly

away within the text. Comets are hirsute, and so is Boylan. In

Lestrygonians Nosey Flynn says, "O, by God, Blazes

is a hairy chap." In Hades Jack Power spots him

from the carriage "airing his quiff"––i.e., doffing his

hat to expose his hair to the air. In Circe Bello says

of Boylan, "He's no eunuch. A shock of red hair he has

sticking out of him behind like a furzebush! Wait for

nine months, my lad! Holy ginger, it's kicking and coughing up

and down in her guts already!" This sentence pins a tail on

Boylan, animalistically phallic but also comet-like, and it

associates the shape with sexual potency.

Hairiness is innately bound up with sexuality, as Circe

makes clear when the Nymph says that she and the stonecold

pure goddesses that Bloom scrutinizd in the National Museum

have "no

hair there." Bloom's rejection of this asexual ideal

associated with John Ruskin means that "a hairy chap" like

Boylan is inhairently threatening. This fear surfaces soon

afterward in Circe when Lenehan "officiously

detaches a long hair from Blazes Boylan's coat shoulder."

Not content to remark on head hairs, Lenehan proceeds to evoke

ones farther down: "Ho! What do I here behold? Were you

brushing the cobwebs off a few quims?" (Boylan, that is

to say, has been putting dusty vaginas back in working order.)

Boylan also is associated with the heavens. Wandering

Rocks notes his "skyblue tie" and his "socks with

skyblue clocks," and when the carriage arrives at 7 Eccles

Street in Sirens "Dandy tan shoe of dandy Boylan socks

skyblue clocks came light to earth." As a comet

approaches perihelion near earth, it lights up and becomes

light, hairy, diaphanous. "Clocks" were designs

embroidered on Victorian and Edwardian socks, but the

clocklike regularity of comets in the sky surely is intended

here.

The name "Boylan" suggests the sun's heat boiling away

water vapor from a comet, and "Blazes" is no less

evocative. Comets look like blazing fireworks, and the word

can also mean "a broad white stripe running the length of a

horse's face," or a similar rectangular "mark made on a tree

by cutting the bark so as to mark a route." In Oxen of the

Sun, a nebula-like apparition appears to draw on both

sorts of meaning: "It floats, it flows about her starborn

flesh and loose it streams, emerald, sapphire, mauve and

heliotrope, sustained on currents of cold interstellar wind,

winding, coiling, simply swirling, writhing in the skies a

mysterious writing till, after a myriad metamorphoses of

symbol, it blazes." This signifying apparition "looms,

vast, over the house of Virgo"––Molly's birth sign.

Many people once detected evil omens in comets, as in

Calpurnia's warning to Caesar: “When beggars die there are no

comets seen; / The heavens themselves blaze forth the

death of princes” (Julius Caesar 2.2.30-31). Such

fears were still alive when Halley's comet reappeared in 1910,

prompting Sir

Robert Ball, in an interview published on the front page

of the 17 May 1910 Bismarck Daily Tribune, to "set at

rest the fears of a grand catastrophe in the minds of those

folks who have been led to believe the comet contains

mischief-making potentialities." Responding to numerous

letter-writers, Ball noted that "a rhinoceros in full charge

would not fear collision with a cobweb, and the Earth need not

fear collision with a comet. In 1861 we passed through the

tail of a comet. No one knew anything about it at the time."

There is no reason to suppose that Joyce shared the popular

superstition about comets being portents, but he certainly

deployed it symbolically in his novel, using comet images to

suggest that Bloom's sexual reign at Eccles Street may be

coming to an end. The adulterer's blazing, boiling approach to

the sun implies Bloom's displacement, as is emphasized in Ithaca

when he imagines leaving home and wandering the earth in

emotional and perhaps financial destitution. In one paragraph

these thoughts of banishment are mapped onto the orbit of a

comet as it leaves behind the heat and light of the sun and

ventures to the cold edges of the known universe. But the

logic of the metaphor implies that one day, "suncompelled,"

Bloom will return from his "selfcompelled" exile:

Ever he would wander, selfcompelled, to the

extreme limit of his cometary orbit, beyond the fixed stars

and variable suns and telescopic planets, astronomical waifs

and strays, to the extreme boundary of space, passing

from land to land, among peoples, amid events. Somewhere

imperceptibly he would hear and somehow reluctantly,

suncompelled, obey the summons of recall. Whence, disappearing

from the constellation of the Northern Crown he would somehow

reappear reborn above delta in the constellation of Cassiopeia

and after incalculable eons of peregrination return an

estranged avenger, a wreaker of justice on malefactors, a dark

crusader, a sleeper awakened, with financial resources (by

supposition) surpassing those of Rothschild or the silver

king.

Having entertained the thought of such a triumphant return

Bloom quickly dismisses it, reflecting that while space may be

"reversible" time is not. (Nor is he likely to discover those

great riches, or to find himself transformed into a violent

avenger.) Nevertheless, this description of a "cometary orbit"

does insinuate thoughts of reversal and cyclicality. Thoughts

of falling to rise again preoccupied Joyce in the Wake, and

there is no doubt that at the end of Ulysses he was

already pondering them. After Bloom drops off into blackness

at the end of Ithaca, Molly's huge looping orbits of

thought distance her for a time from her husband but finally

bring her back to him––on Howth, in the sunshine, savoring

sexual pleasure.