The macintosh, often spelled "mackintosh" as in Oxen

of the Sun, was a heavy-duty raincoat named after

Scottish chemist Charles Macintosh, who in 1824 came up with

the idea of using naphtha to bond a layer of rubber between

two layers of cotton cloth. The mention of such a coat is

itself puzzling. Ireland has notoriously wet weather, so going

out with a raincoat or umbrella normally makes sense. In Calypso

Bloom thinks, "Hallstand too full. Four umbrellas, her

raincloak." But on the morning and afternoon of 16 June

1904 Dublin is sunny and warm, and there have been weeks of

drought. Much later in the day a violent rainstorm blows

through the city, catching many people off guard, but one man

is ready for it, dressed stoutly in an unbreathable garment

that would be stifling in the noontime heat. Does he somehow

foresee the torrential rain? Is he a traveler who routinely

wears a rubberized coat to be prepared for rain? Is he infirm

and vulnerable to chills?

Bloom's physical descriptors are also intriguing. "Lanky"

people are tall and skinny. A "galoot" is unkempt or

clumsy-looking, and in Ireland, Dolan notes, "an awkward,

stupid man; a fool." Combined, the two words suggest a figure

who is gaunt, dishevelled, pathetic, out of place in the

well-dressed decorum of the cemetery. These impressions are

confirmed and amplified at the end of Oxen when, in

the whirl of words in Burke's pub, people remark upon an

odd-looking stranger:

Golly, whatten tunket's yon guy in the mackintosh?

Dusty Rhodes. Peep at his wearables. By mighty! What's he got?

Jubilee mutton. Bovril, by James. Wants it real bad. D'ye ken

bare socks? Seedy cuss in the Richmond? Rawthere! Thought he

had a deposit of lead in his penis. Trumpery insanity. Bartle

the Bread we calls him. That, sir, was once a prosperous cit.

Man all tattered and torn that married a maiden all forlorn.

Slung her hook, she did. Here see lost love. Walking

Mackintosh of lonely canyon. Tuck and turn in. Schedule time.

Nix for the hornies. Pardon? Seen him today at a runefal? Chum

o' yourn passed in his checks?

The question, "

Chum o' yourn passed in his checks?"

(i.e., died), must be directed to Bloom, the only man in the

group of drinkers who could have "

Seen him today at a runefal."

A discreet "

Peep at his wearables" shows that he is "

tattered

and torn" like the man in the

nursery rhyme. His socks are

thread-"

bare," and his coat looks like he has been

walking down long "

Dusty Rhodes." Gifford identifies a

person of this name as "an American comic-strip character from

about 1900, the tramp who weathers continuous comic misfortune,"

and he suggests that the following moniker, "

Walking

Mackintosh of lonely canyon," echoes the titles of

"American dime-novel Westerns." In a

JJON note, John

Simpson supports Gifford's gloss, observing that the Dusty

Rhodes character began to appear in American newspapers "around

1891" and in cartoons several years later, including some in a

British comic magazine called

Illustrated Chips which

was stocked by the Dublin newsagent Tallon's in 1898.

Dusty Rhodes was a battered-looking old tramp, and Joyce's man

in the macintosh fits that mold. He looks not only poorly

dressed but half-starved. "

Jubilee mutton" refers to the

unsatisfyingly small portions of free mutton given to Dublin's

poor during Queen Victoria's 1897 Jubilee visit. "

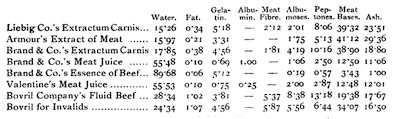

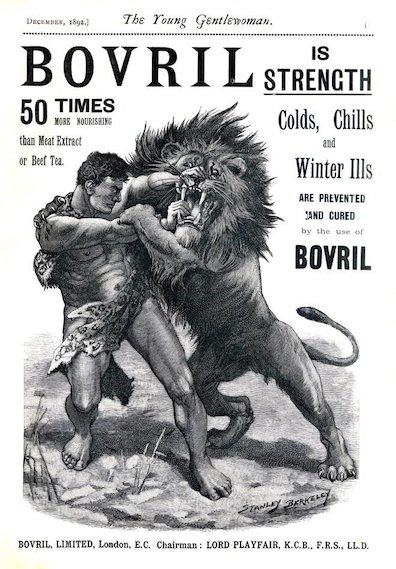

Bovril"

beef tea, which was widely advertised as a restorative tonic for

the infirm, seems in order: he "

Wants it real bad." The

phrase could mean either that the man craves the broth or that

he needs it, a distinction without a difference. Apparently he

is known to certain people as "

Bartle the Bread" (Slote

cites two entries in Joyce's

Oxen notesheets suggesting

sources of this expression) because he habitually chews on

pieces of bread––a habit confirmed in a passage at the end of

Wandering

Rocks that will be mentioned in a moment.

In addition to these physical details the

Oxen passage

suggests that someone in the group of medical students knows

something of the stranger's life story, apparently because he

treated or at least saw a "

Seedy cuss in the Richmond"

Asylum

who was suffering from delusions: "

Thought he had a deposit

of lead in his penis." (Slote cites a sentence in Joyce's

notesheets for

Oxen that connects this detail to Spanish

fly, an aphrodisiac: "Chap thinks he has swallowed fly, deposit

of lead in penis.") If the man was indeed committed to a mental

hospital and subsequently released, this would be a case of "

trumpery

insanity," i.e., temporary insanity. Apparently he had a

nickname within the walls of the institution: "Bartle the Bread

we calls him." The medico does not know the bedraggled

man's name, but he knows that he was once well-off and fell on

hard times: "

That, sir, was once a prosperous cit."

And then this speaker adds an even more distinctive biographical

detail. Recalling several more words from

The House that

Jack Built, he says that the man all tattered and torn "

married

a maiden all forlorn.

Slung her hook, she did. See

here lost love." The man apparently descended into

insanity because his wife, a deeply unhappy woman, died or

otherwise left him. He is a walking example of the pain of lost

love. Although the speaker does not say how he knows these

things, one can imagine a hospital attendant hearing them said

of a patient, and if true they would account for the man's visit

to the graveyard. Lest anyone doubt this reading, Joyce supplies

a confirmatory detail in

Cyclops: "

The man in the

brown macintosh loves a lady who is dead." This sentence

occurs in one of the chapter's wildly parodic passages, but

another detail in that passage ("Gerty MacDowell loves the boy

that has the bicycle") is shown to be accurate in the following

chapter.

Hades offers one more striking detail: the man seems

spectral. Bloom first spots him while the funeral party is

standing around Dignam's grave:

Mr Bloom stood far back, his hat in his hand,

counting the bared heads. Twelve. I'm thirteen. No. The chap

in the macintosh is thirteen. Death's number. Where the deuce

did he pop out of? He wasn't in the chapel, that I'll swear.

Silly superstition that about thirteen.

The stranger may have joined the funeral party out of

sympathetic curiosity, wandering over from a nearby grave to

observe, but if so, why did the observant Bloom not notice his

approach? His sudden appearance feels almost ghostly: "

Where

the deuce did he pop out of?" Later, when Bloom looks

around for the man in response to a question from Joe Hynes, he

has vanished just as abruptly, which would be hard to do in the

open spaces of the cemetery: "

Where has he disappeared to?

Not a sign. Well of all the....

Become invisible. Good

Lord, what became of him?" The impression of ghostliness

is reinforced at the end of

Wandering Rocks when someone

dashes in front of the viceroy's carriage: "

In Lower Mount

street a pedestrian in a brown macintosh, eating dry bread,

passed swiftly and unscathed across the viceroy's path."

Crossing the street in front of a team of horses is

life-threatening. Is the man exceptionally surefooted to brave

death in this way, or does he not have to worry about death

anymore?

The spookiness is augmented by Bloom's numerology. He counts

heads around the grave and reflects, "

I'm thirteen. No. The

chap in the macintosh is thirteen. Death's number." The

belief that thirteen people in a group foretells death was

traditional. Slote cites Mary Colum's testimony that Joyce took

the belief seriously, once becoming highly agitated when the

imminent addition of two more people to a gathering promised to

make a total of thirteen (

Our Friend James Joyce, 133).

Brewer's Dictionary cites a

Spectator article,

"On Popular Superstitions," in which Joseph Addison recalls

being in "a mixed assembly that was full of noise and mirth,

when on a sudden an old woman unluckily observed there were

thirteen of us in company. This remark struck a panic terror

into several who were present," until a quick-witted friend

reassured the fearful women that, since one of them was

pregnant, they were really fourteen and so no one was going to

die. Like Addison, Bloom regards the fear as a "Silly

superstition," but it is deeply enough engrained in him that he

reflexively counts heads. The taboo apparently was inspired by

Christ holding a Last Supper with his twelve disciples just

before his betrayal and death. Judas is usually seen as the

deadly thirteenth at that gathering, and Bloom regards the

macintosh man in the same way.

In

Circe, where sudden apparitions and disapparitions

are commonplace, the man again performs his ghostly trick just

as Bloom's apotheosis nears its highest pitch:

(A man in a

brown macintosh springs up through a trapdoor. He points

an elongated finger at Bloom.)

THE MAN IN THE MACINTOSH: Don’t

you believe a word he says. That man is Leopold M’Intosh,

the notorious fireraiser. His real name is Higgins.

BLOOM: Shoot him! Dog of a

christian! So much for M’Intosh!

(A cannonshot. The man

in the macintosh disappears. Bloom with his

sceptre strikes down poppies. The instantaneous deaths

of many powerful enemies, graziers, members of parliament,

members of standing committees, are reported....)

The trap door suggests an allusion to

Hamlet, since the

ghost in that play, after speaking with Hamlet, exits through

such a device in the stage floor, prompting the prince to refer

to "this fellow in the cellarage" (1.5.151), "old mole" (162),

"A worthy pioner!" (163). In Joyce's recasting of the scene the

ghostly figure comes to accuse Bloom rather than Claudius, and

it charges him with false identity rather than murder. Giving

Bloom the name "

Leopold M'Intosh" allies him with the

ghostly figure just as tightly as the name Hamlet allies the

prince with his ghost. And since Bloom's mother was Ellen "

Higgins,"

maternity too is involved.

The name "M'Intosh" has a comical birth in

Hades when

newspaper reporter Joe Hynes, compiling a list of mourners, asks

Bloom about the man "over there in the..." Bloom completes the

sentence with the name of the raincoat but Hynes misunderstands

and writes down "M'Intosh." Newspapers not only describe

reality; they create it. In the

Evening Telegraph that

Bloom peruses in

Eumaeus one person has been changed

into another (L. Boom), two people not present at the funeral

have attended it (Stephen Dedalus and Charley

M'Coy), and

one person who was anonymously present has acquired a name.

Since that name is clearly fictive, Joyce encourages his readers

to identify "

His real name," just as he does with Martha

Clifford.

Bloom ponders this question throughout the novel. In

Hades

he thinks, "

Now who is he I'd like to know? Now I'd give a

trifle to know who he is. Always someone turns up you never

dreamt of." In

Sirens he wonders again who the man

may be, just after marveling that

the croppy boy did not spot the

British soldier in the priest's garments: "All the same he must

have been a bit of a natural not to see it was a yeoman cap.

Muffled up.

Wonder who was that chap at the grave in the

brown macin." If the boy was not mentally deficient, Bloom

thinks, perhaps he failed to recognize the yeoman because his

face was "Muffled up." And then he thinks of the "chap at the

grave." Does he do so because he had trouble viewing that man's

face? These moments of speculation about the macintosh man's

identity lead to a final posing of the question in

Ithaca,

the chapter where Joyce also challenges his readers to "

find M. C."

Three mysteries preoccupy Bloom as he prepares for bed. The

second, "

selfinvolved enigma" is "

Who was M'Intosh?"

These clear invitations to solve a mystery have prompted a

blizzard of hypotheses from Joyce's critics. M'Intosh, some say,

is James Joyce. He is Bloom's doppelganger. He is Jesus Christ.

He is Death, or Hades. He is the god Hermes. He is Theoclymenos,

who predicts the suitors' deaths in the

Odyssey. He is

Wetherup, a workplace associate of John Stanislaus Joyce. He is

James Clarence Mangan, 19th century Irish poet. He is Charles

Stewart Parnell, 19th century Irish politician. He is James

Duffy from

the story "A Painful Case," or Mr. Sinico

from that story. These last two possibilities are somewhat

plausible, since Duffy did love

a lady who died, and she was

very unhappy. But Duffy was not married to Emily Sinico, and her

husband did not love her much. Other proposed solutions fall

much farther short of the mark. Responding to one or two pieces

of the puzzle, they ignore all the rest, and most of them, if

adopted, would not add anything to one's understanding of the

novel's action.

Only one really thorough, careful, and plausible interpretation

has yet been offered. In two articles and a section of a

book––"The M'Intosh Mystery,"

Modern Fiction Studies 29

(1983): 671-79; "The M'Intosh Mystery: II,"

Twentieth

Century Literature 38 (1992): 214-25; and

Joyce and

Reality: The Empirical Strikes Back (Syracuse UP,

2004) pp. 237-49––John Gordon argues that Joyce has constructed

a Sherlock Holmes-like whodunit, "set up to tease the reader

into thought as deliberately as any Agatha Christie" (2004:

238). (Wilkie Collins' detective novel

The Woman in White,

which Miss Dunne is reading in

Wandering Rocks, also

seems relevant, since its title resembles The Man in the

Macintosh and the titular figure has escaped from an asylum and

is wandering about London. The nameless woman in that novel does

turn out to be identifiable.)

A mystery challenges its readers to become detectives, ideally

supplying enough clues for smart and determined ones to crack

the case themselves. Another premise of the genre, according to

Gordon: "If there is one point on which all writers and readers

of mysteries agree, it is that you do not solve the riddle

ex

machina: the culprit ought to be someone in the book, at

least by allusion" (1983: 673). Operating on this principle,

Gordon looks for distraught widowers in Joyce's fictions and

finds only two. One is Simon Dedalus, who cannot be the mystery

man because he is in the funeral party. The other is Bloom's

father Rudolph, who committed suicide and left behind a note

telling his son how terribly he missed his dead wife and longed

to be reunited with her.

Crediting this reasoning would, of course, make the stranger a

dead man, but Gordon quotes a principle voiced by Edgar Allen

Poe's detective Auguste Dupin (and later repeated by Arthur

Conan Doyle's Sherlock Holmes): "when you have eliminated the

impossible, then what remains must be true" (2004: 240). He also

cites Joyce's interest in various kinds of spiritualism,

including séances, and the fact that he and his sister once

stayed up late at night to see their mother's ghost. It is not

difficult to imagine Joyce playing with the possibility of a

ghostly visitation in his fiction, given the way he sprinkles

themes of death-in-life and life-in-death throughout

The

Dead and

Hades. In

Scylla and Charybdis

Stephen reads

Hamlet as a kind of "

ghoststory."

If Shakespeare can show a man returning from the dead to visit

his son, why not Joyce?

Rudolph Bloom was buried in County Clare after committing

suicide in the Queen's Hotel in Ennis, so his ghost, if such it

is, has strayed far to be beside his Ellen, whom Bloom reflects

is buried "

over there towards Finglas," i.e., in the

western part of the Glasnevin cemetery. Ghosts traditionally

were said to travel great distances, and also, Gordon observes,

to do seemingly incongruous things like eating and taking public

transportation. In the early 20th century, one was even said to

have worn a macintosh. The dead people most likely to return as

ghosts were

murder

victims and suicides––which is why Bloom thinks in

Hades,

"

They used

to drive a stake of wood through his heart in the grave,"

to keep the suicide from coming back. The discussion of suicide

in that chapter also specifically evokes the man in the

macintosh. Martin Cunningham charitably excuses suicide with the

phrase "

Temporary insanity," the same phrase used in a

garbled way in

Oxen. The fact that this man craves

Bovril beef broth further associates him with ghosts, because in

the

Odyssey the wraithlike dead are revivified by

drinking the blood of slaughtered cattle.

Numerous details beyond the suicide link this ghost with Bloom's

father. Rudolph Bloom was once "a prosperous cit": he bought the

Queen's Hotel before suffering financial ruin. In

Circe

Bloom thinks "I am ruined" while contemplating Rudolph's suicide

in the hotel, and in

Penelope Molly recalls that he too

once talked of running a hotel: "Blooms private hotel he

suggested

go and ruin himself altogether the way his father

did down in Ennis." Bloom's occasional leg pains explain

why his father's ghost might show up in rainwear on a day that

starts hot and dry but eventually proves rainy: he says in

Circe

that "I have felt this instant a twinge of sciatica in my left

glutear muscle. It runs in our family.

Poor dear papa, a

widower, was a regular barometer from it." In addition,

the "

elongated finger" that the trapdoor man points at

Bloom may recall Bloom's vivid memory of his father in

Aeolus:

"Poor papa with

his hagadah book,

reading

backwards with his finger to me."

Finally, the name of the Dusty Rhodes cartoon character echoes

again and again. Rudolph Bloom was a traveling salesman, so this

tramp is a fitting avatar for him. The narrator of

Cyclops

thinks of Bloom's "old fellow" as having been "like Lanty

MacHale's goat that'd

go a piece of the road with every

one." The fantastical biblical genealogy applied to Bloom in

Circe

includes Dusty as a progenitor: "Moses begat Noah and Noah begat

Eunuch and Eunuch begat O'Halloran and O'Halloran begat

Guggenheim and...

ben Maimun begat Dusty Rhodes and Dusty

Rhodes begat Benamor..." Several pages later in the same

chapter Bloom appears as a wandering peasant dressed in "

dusty

brogues" and plans to reenact his father's suicide: "I am

ruined. A few pastilles of aconite. The blinds drawn. A letter.

Then lie back to rest."

At a still finer level of granular detail, Gordon observes that

the choice of one morpheme evokes the ghost's paternal relation

to Bloom. Amazed by the apparition in the cemetery, Bloom

wonders, "Where the deuce did he

pop out of?" It might

seem falsely associative to take the word in this way, but

Gordon observes that in private and in his notebooks for

Finnegans

Wake Joyce used "Pop" more frequently than any other term

for "father." Fathers are the original authority figures, so it

is interesting to hear the same word used in an Oedipal context

in the trapdoor passage in

Circe. Accused by M'Intosh of

being M'Intosh, "

Bloom with his sceptre strikes down

poppies" just before the deaths of various authority

figures are reported. Slote cites the legend of Roman king

Lucius Tarquinius Superbus striking off the heads of poppies as

a coded instruction to put to death the chief men in the

rebellious town of Gabii. It seems very likely, then, that Bloom

here is enacting a fantasy of killing off his pop.

Seen in the context of patriarchal authority and Oedipal

rebellion, other details in the

Circe passage make

clearer sense. Bloom's real names are "

M'Intosh" and "

Higgins"

because M'Intosh begat him upon Higgins. (As a "

seedy cuss,"

he recalls biblical patriarchs like Abraham and Jacob whose

"seed" was multipied.) Bloom may not seem like a "

fireraiser"

now, but in his adolescent rebellious phase he probably appeared

that way to his father when, as

Ithaca notes, he

advocated radical political positions and disrespected certain

Jewish "beliefs and practices." The ghostly figure can denounce

him as a fraudulent impostor and Bloom can call his accuser "

Dog

of a Christian!" (Rudolph's beloved dog Athos may lurk

here) because both men are Jews who have tried to pass as

Christians, and Bloom is

a Jew whose mother is not Jewish.

Multiple layers of kinship, guilt, sympathy, and accusation

underlie the connection of the two M'Intosh men.

Claud Sykes, an American friend of Joyce’s in Zurich, reported

that he liked to ask friends the playful question, "Who was the

man in the mackintosh?" Richard Ellmann too mentions these

interrogations (516). Joyce's intent in asking the question may

be construed in different ways. Did he want to see how well

readers had undertaken their detective work, or did he wonder

what others thought because he was uncertain himself? Some

critics have opted for the latter view. In 1962 Robert Martin

Adams wrote in

Surface and Symbol that "Joyce has only

to play with this unfulfilled curiosity, and to refrain from

satisfying it." If the answer is someone as insignificant as

Wetherup, he says, "we may be excused for feeling that the fewer

answers we have for the novel's riddles, the better off we are.

As with Stephen's shaggy-dog riddle at the school, the puzzle is

less puzzling than the answer" (218). (Adams does not ponder the

fact that this riddle in

Nestor is connected with

Stephen's anxiety at being

haunted by the ghost of his mother.)

A quarter of a century later, Phillip Herring felt that Adams'

view was still valid. In

Joyce's Uncertainty Principle

(1987) he wrote that M'Intosh is only a "deceitful ploy to keep

us guessing" (117). Gordon had published his first M'Intosh

article in 1983, and Herring aggressively attacked its argument.

In his 1992 sequel Gordon responded convincingly to the

objections, noting by the way that he never claimed certainty

for his hypothesis: "In

Ulysses one deals, usually, not

with distinctly demarcated realms of known and unknowable, but

with relative degrees of exactness and probability. When I first

wrote 'The M'Intosh Mystery', I would most likely have put the

probability of its thesis at around seventy percent. I'd rate it

a good deal higher now...because in the person of Philip Herring

an astute critic has challenged it without, I think,

successfully undoing any of its arguments" (1992: 219). Gordon

has continued to assemble supporting arguments and to address

some of the grounds for skepticism, including the question of

why Bloom would not recognize his own father. His theory may

compel less than one hundred percent certainty, but it is still

by far the most powerfully explanatory one out there.

Gordon's answer to the question "Now who is he I'd like to

know?" not only accounts for a wealth of textual details. It

also fits squarely within the novel's governing narrative

structures. Stephen approaches

Hamlet as the story of a

dead father returning to give purpose to his bewildered son, and

he too is a son searching for that kind of purpose, so readers

are led to expect that he may discover some of what he seeks in

Bloom. But Bloom is not only a father figure. He is also a son,

and unlike Stephen he has actually lost his father. He too wears

black on June 16, like Hamlet, and like the prince he is

troubled by the manner of his father's death. It makes literary

sense for him to be haunted as Hamlet is.

The search for paternal significance also informs the classical

epics that Joyce is working with. In book 6 of the

Aeneid,

echoed often

in

Hades, Aeneas visits the land of the dead to speak

with his father and learn his destiny from him. In the

Odyssey

the protagonist is a lost father returning to Ithaca to form an

alliance with his son, but also a son seeking reunion with his

aged father. Joyce listed Laertes as a Homeric analogue in his

Linati

schema,

Gordon notes, and the only character in the graveyard to whom he

might correspond is the man in the macintosh. Where does

Odysseus find his father? Sitting in the middle of a road,

covered in dust, grieving his wife's death. Bloom's connections

to the

Odyssey as to

Hamlet are strengthened by

recognizing his kinship to the man in the macintosh.

A coda: in a third article, "The M'Intosh Murder Mystery," Journal

of Modern Literature 29 (2005): 94-101, Gordon returned

to his theory one last time, recapping the points made in

earlier publications and adding to them a new speculation that

he admits is "alarmingly lurid and louche and just all-around

weird" (94). In this essay he ventures to explain how Rudolph

Bloom's wife may have died and why he thought he had "a

deposit of lead in his penis." At the tail end of an

exceptionally long note, that argument can be reserved for another

place.